After a short sabbatical from public service, I’m delighted to announce I’m returning to the Australian Public Service, where I intend to do my part in the extraordinary and once-in-a-generation reform agenda currently under way 😊

I have had wonderful opportunities over the past 23 years to work with and in the public sector, but it was 15 years ago that I really committed my professional life and career to public sector reform. I’ve since built up a broad and deep understanding of good public administration, while also acting as an enthusiastic pathfinder to shape modern, innovative and evidence-based approaches with adaptive operating models for more humane and participatory public policy, services and governance.

As part of this journey, and for those who want to understand my move to AWS, I decided to take a “public sector sabbatical” at the beginning of last year. I had three goals:

- to immerse myself in the challenges and opportunities of AI for government;

- to see whether it was possible to systemically help the tech sector be more mission-oriented and cognisant of the unique context of public service; and

- to explore ways to close the gap between policy design and delivery.

I was extremely lucky to be offered a role in a special team at Amazon Web Services (AWS) where I have not only been encouraged, but supported to explore these wicked problems, while also being able to share and learn along the way. It was great to work for a large tech company that is genuinely committed to helping their clients to grow and succeed, including the necessary internal capability and confidence in modern tech, mindsets and design/delivery methods. I also got to work with some extraordinary colleagues and a wonderfully visionary boss 😊 A huge thank you to Bruce Haefele, Amity Durham, Jithma Beneragama, Tim Bradley and Jodi Philips in the AWS Strategic Development team, along with all the other wonderful people I got to collaborate with. If you’re looking for AWS folk who really understand both gov and tech, Bruce and the team are great 😊 Thanks for the opportunity!

So I’m delighted to say I was able to do some great work on a whole range of projects while also making progress on all three of my professional goals:

- Trustworthy AI in government – I wrote a paper on building trustworthy AI systems in government, with a special focus on ADM (Automated Decision Making), with a wonderful range of reviewers and contributors with expertise on AI, public administration, privacy/law, ethical IT, social policy and more. It’s called the “A Trust Framework for Government Use of Artificial Intelligence and Automated Decision Making” and was followed by a range of talks, blogs and other thought leadership, which goes to the heart of ensuring any AI system isn’t just designed ethically, but it operated, continuously improved and monitored for real and unintended impacts. I also got to work with the wonderful AI expert, Natacha Fort, to create a comprehensive range of AI usage patterns, which really help to understand the different ways AI can be used, and their different risk and mitigation strategies for government.

- Mission/policy-oriented tech and delivery – After starting at AWS I learned about the Well-Architected Framework, which is the technical assurance mechanism adopted for all AWS systems globally. So we formed a diverse and international team to design an expansion pack, a “lens” with best practices and recommendations to ensure the special context and requirements of government – including the policy intention – are all included in the design, delivery and operating models for public sector systems/services. This provides a useful means for tech/IT teams to reach across the aisle to policy/business/regulatory teams and help close the gap between policy design and delivery. You can find the Gov Lens for the AWS Well-Architected and the Gov Lens is also available in the Well-Architected Tool for those wanting to use it for early definition/requirements gathering or to assure new systems.

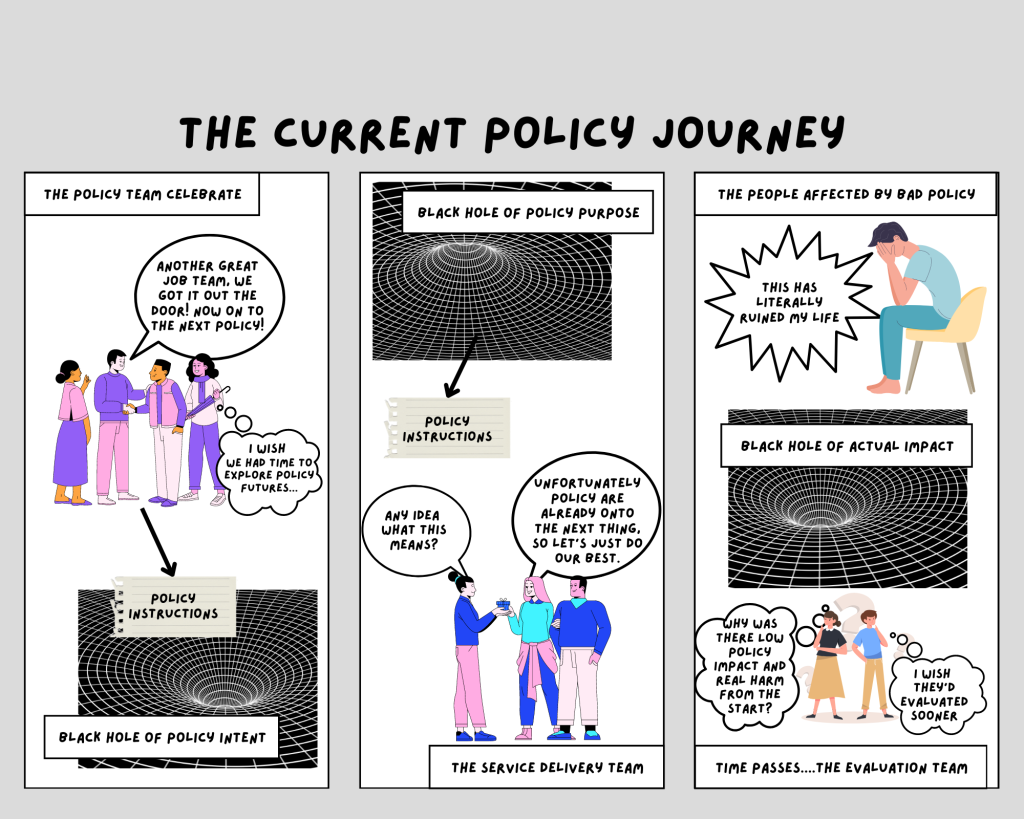

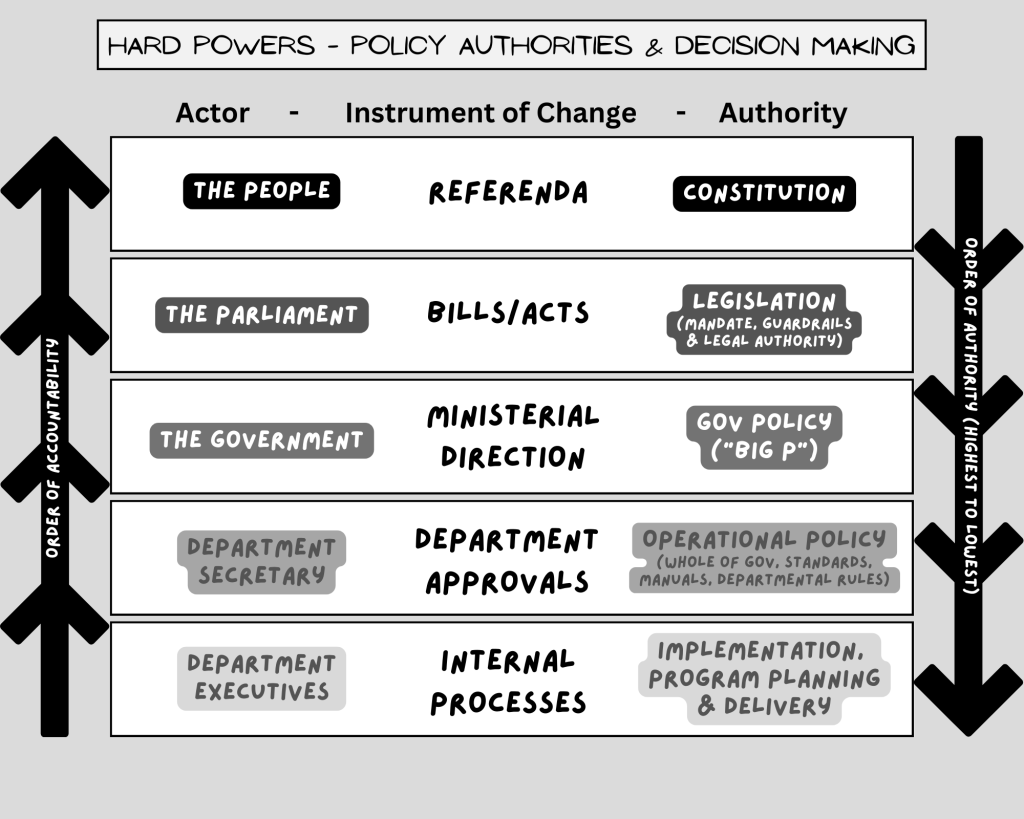

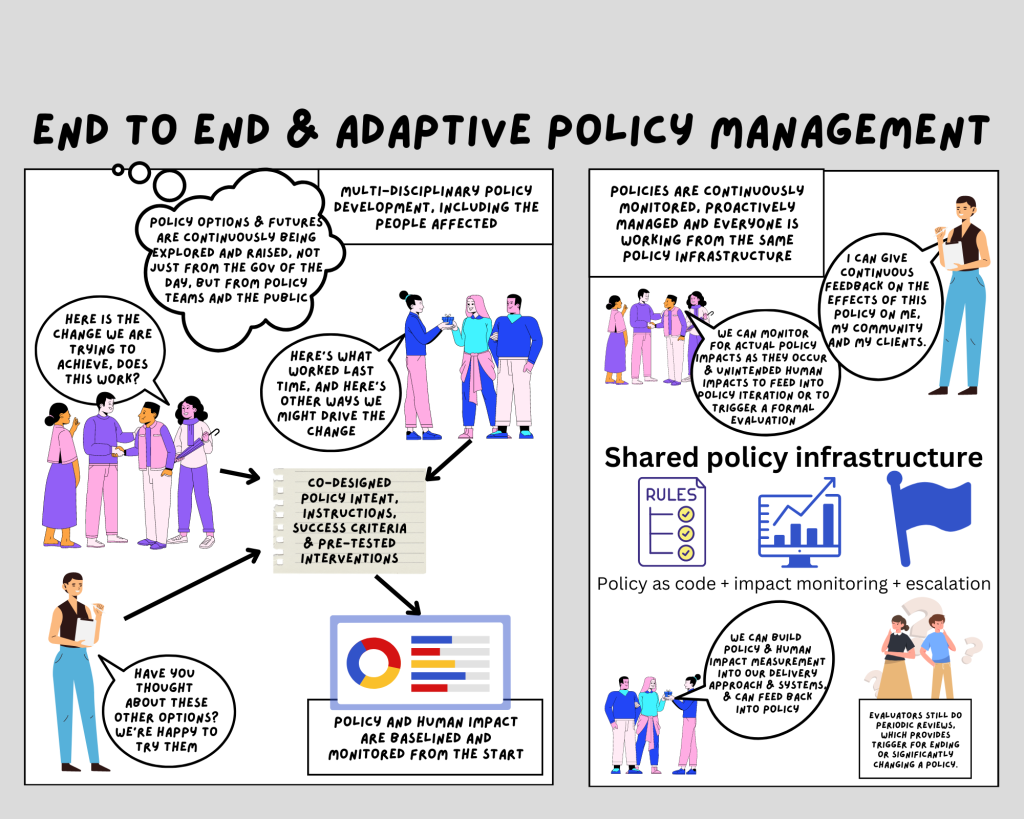

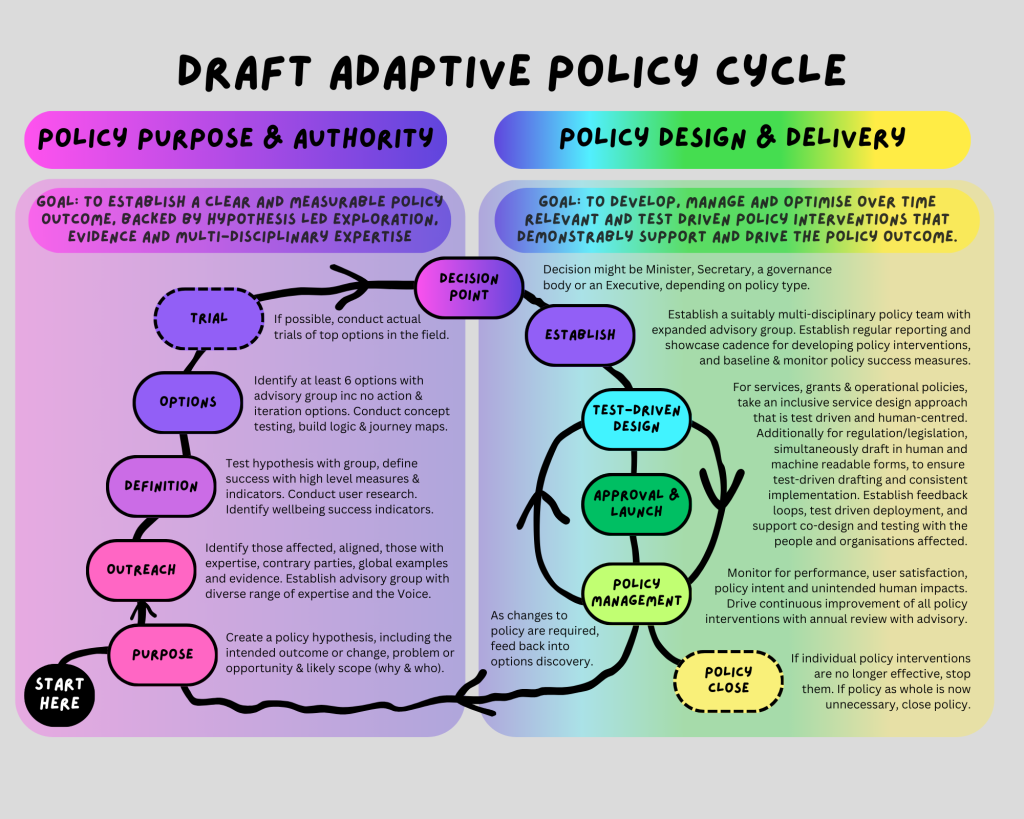

- Adaptive policy management – My final goal was to explore and hopefully help establish a more adaptive, end-to-end and humane approach to policy design, decision making, delivery and continuous improvement. This journey led to an extraordinary collaboration with Prof Anna Zhu, an incredible researcher and lecturer at RMIT, which provided a platform for many areas of collaboration and progress. Anna and I brought together a diverse and wonderful group of research organisations, NGOs, government departments and companies that work with government, to submit an ARC Linkage Grant which was funded last month. The research project is called “The Intended and Unintended Impact of Policy for Adaptive Policy Management” and has two parts: 1) hypothesis-led research into how possible it is to monitor for and understand the patterns of human impact from policy changes using existing and cross sector data, with a reasonably high scientific and statistical confidence; and 2) to use the insights and learning from part one to inform a test-driven human impact measurement framework, a new adaptive policy cycle and operating model, and a range of policy infrastructure prototypes and demonstrators to enable end-to-end adaptive policy management. This collaboration has led to work through the year to explore the problems, opportunities and better/worse futures for policy management. I’ve written about some of our findings on the case for more adaptive policy management, and the case for shared and end-to-end policy infrastructure, and you can see sessions with Prof Catherine Althaus here and with Thea Snow here. Catherine, Thea, Suhit Anantula and I are trying to distill some of the work into a book over the coming year or so which will provide new policy frameworks and guidance for the whole sector 😊

My last reflection, is that I went to AWS because I wanted to continue working on public sector reform, even if from a position outside of service for a short spell, and I wanted to work specifically for an organisation that was aligned with my goal. AWS has, at its heart, a “customer obsession” which enables the company to systemically want to help clients to succeed and be highly capable, which is not always the case. So while some people were confused with my choice of sabbatical, hopefully the above helps to provide some context 😊

Now to the next chapter!

I’m very excited and humbled to announce I’ll soon be the Chief Data Officer in the Data and Economic Analysis Centre (DEAC) at the Department of Home Affairs. From all I can see, DEAC is one of the top data capabilities in the APS, and the portfolio does challenging and important work so I hope to bring my passions for great CCX service delivery (Client and Citizen/resident/refugee/migrant Experience), for humane and trustworthy end-to-end policy design and delivery, and of course, for data and evidence-driven decision making and continuous improvement, to the table. Perhaps we could also be a global exemplar for policy infrastructure 😉 I am delighted to be reporting to Deputy Secretary Sophie Sharpe, and to be in a position to contribute to the APS Reform in a department that is extremely committed to the agenda. I also look forward to rejoining the APS, especially with the benefits, lessons and experience from my time in the New Zealand, NSW and Canadian Governments.

Coming back to the APS feels like I’m coming home. It is all the more exciting for the once-in-a-generation changes happening at all levels to become a better public sector for everyone, and I intend to do my part to help.