On the eve of moving to Ottawa to join the Service Canada team (squee!) I thought it would be helpful to share a few things for posterity. There are three things below:

- Some observations that might be useful

- A short overview of the Pia Review: 20 articles about digital public sector reform

- Additional references I think are outstanding and worth considering in public sector digital/reform programs, especially policy transformation

Some observations

Moving from deficit to aspirational planning

Risk! Risk!! Risk!!! That one word is responsible for an incredible amount of fear, inaction, redirection of investment and counter-productive behaviours, especially by public sectors for whom the stakes for the economy and society are so high. But when you focus all your efforts on mitigating risks, you are trying to drive by only using the rear vision mirror, planning your next step based on the issues you’ve already experienced without looking to where you need to be. It ultimately leads to people driving slower and slower, often grinding to a halt, because any action is considered more risky than inaction. This doesn’t really help our metaphorical driver to pick up the kids from school or get supplies from the store. In any case, inaction bears as many risks as no action in a world that is continually changing. For example, if our metaphorical driver was to stop the car in an intersection they will likely be hit by another vehicle, or eventually starve to death.

Action is necessary. Change is inevitable. So public sectors must balance our time between being responsive (not reactive) to change and risks, and being proactive towards a clear goals or future state.

Of course, risk mitigation is what many in government think they need to most urgently address however, to only engage this is to buy into and perpetuate the myth that the increasing pace of change is itself a bad thing. This is the difference between user polling and user research: users think they need faster horses but actually they need a better way to transport more people over longer distances, which could lead to alternatives from horses. Shifting from a change pessimistic framing to change optimism is critical for public sectors to start to build responsiveness into their policy, program and project management. Until public servants embrace change as normal, natural and part of their work, then fear and fear based behaviours will drive reactivism and sub-optimal outcomes.

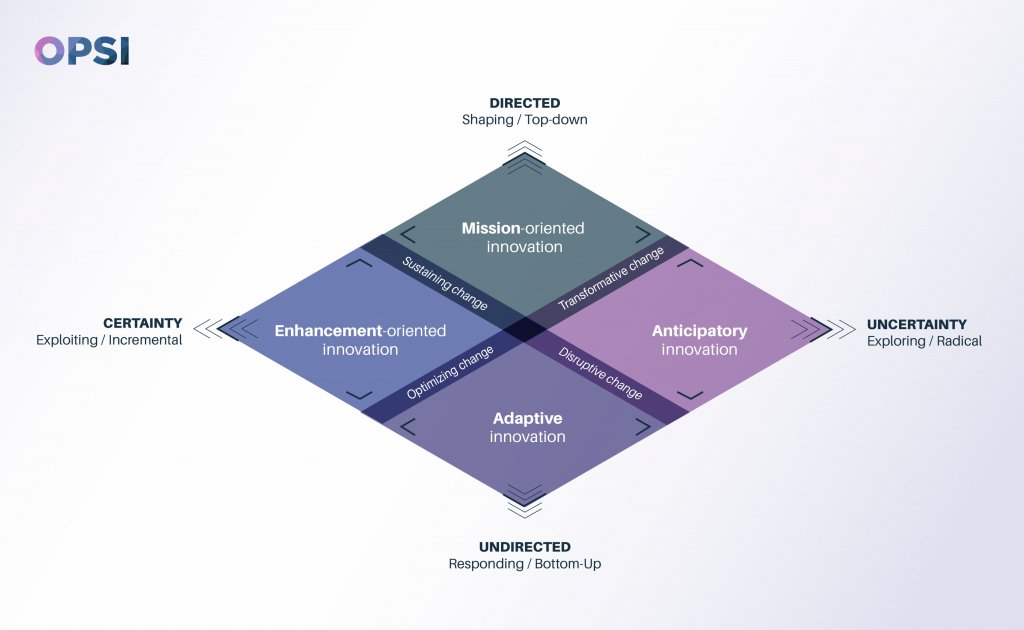

The OPSI model for innovation would be a helpful tool to ask senior public servants what proportion of their digital investment is in which box, as this will help identify how aspirational vs reactive, and how top down or bottom up they are, noting that there really should be some investment and tactics in all four quadrants.

My observation of many government digital programs is that teams spend a lot of their time doing top down (directed) work that focuses on areas of certainty, but misses out in building the capacity or vision required for bottom up innovation, or anything that genuinely explores and engages in areas of uncertainty. Central agencies and digital transformation teams are in the important and unique position to independently stand back to see the forest for the trees, and help shape systemic responses to all of system problems. My biggest recommendation would be for the these teams to support public sector partners to embrace change optimism, proactive planning, and responsiveness/resilience into their approaches, so as to be more genuinely strategic and effective in dealing with change, but more importantly, to better plan strategically towards something meaningful for their context.

My observation of many government digital programs is that teams spend a lot of their time doing top down (directed) work that focuses on areas of certainty, but misses out in building the capacity or vision required for bottom up innovation, or anything that genuinely explores and engages in areas of uncertainty. Central agencies and digital transformation teams are in the important and unique position to independently stand back to see the forest for the trees, and help shape systemic responses to all of system problems. My biggest recommendation would be for the these teams to support public sector partners to embrace change optimism, proactive planning, and responsiveness/resilience into their approaches, so as to be more genuinely strategic and effective in dealing with change, but more importantly, to better plan strategically towards something meaningful for their context.

Repeatability and scale

All digital efforts might be considered through the lens of repeatability and scale.

- If you are doing something, anything, could you publish it or a version of it for others to learn from or reuse? Can you work in the open for any of your work (not just publish after the fact)? If policy development, new services or even experimental projects could be done openly from the start, they will help drive a race to the top between departments.

- How would the thing you are considering scale? How would you scale impact without scaling resources? Basically, for anything you, if you’d need to dramatically scale resources to implement, then you are not getting an exponential response to the problem.

Sometimes doing non scalable work is fine to test an idea, but actively trying to differentiate between work that addresses symptomatic relief versus work that addresses causal factors is critical, otherwise you will inevitably find 100% of your work program focused on symptomatic relief.

It is critical to balance programs according to both fast value (short term delivery projects) and long value (multi month/year program delivery), reactive and proactive measures, symptomatic relief and addressing causal factors, & differentiating between program foundations (gov as a platform) and programs themselves. When governments don’t invest in digital foundations, they end up duplicating infrastructure for each and every program, which leads to the reduction of capacity, agility and responsiveness to change.

Digital foundations

Most government digital programs seem to focus on small experiments, which is great for individual initiatives, but may not lay the reusable digital foundations for many programs. I would suggest that in whatever projects the team embark upon, some effort be made to explore and demonstrate what the digital foundations for government should look like. For example:

- Digital public infrastructure – what are the things government is uniquely responsible for that it should make available as digital public infrastructure for others to build upon, and indeed for itself to consume. Eg, legislation as code, services registers, transactional service APIs, core information and data assets (spatial, research, statistics, budgets, etc), central budget management systems. “Government as a Platform” is a digital and transformation strategy, not just a technology approach.

- Policy transformation and closing the implementation gap – many policy teams think the issues of policy intent not being realised is not their problem, so showing the value of multidisciplinary, test-driven and end to end policy design and implementation will dramatically shift digital efforts towards more holistic, sustainable and predictable policy and societal outcomes.

- Participatory governance – departments need to engage the public in policy, services or program design, so demonstrating the value or participatory governance is key. this is not a nice to have, but rather a necessary part of delivering good services. Here is a recent article with some concepts and methods to consider and the team needs to have capabilities to enable this, that aren’t just communications skills, but rather genuine and subject matter expertise engagement.

- Life Journey programs – putting digital transformation efforts,, policies, service delivery improvements and indeed any other government work in the context of life journeys helps to make it real, get multiple entities that play a part on that journey naturally involved and invested, and drives horizontal collaboration across and between jurisdictions. New Zealand led the way in this, NSW Government extended the methodology, Estonia has started the journey and they are systemically benefiting.

- I’ve spoken about designing better futures, and I do believe this is also a digital foundation, as it provides a lens through which to prioritise, implement and realise value from all of the above. Getting public servants to “design the good” from a citizen perspective, a business perspective, an agency perspective, Government perspective and from a society perspective helps flush out assumptions, direction and hypotheses that need testing.

The Pia Review

I recently wrote a series of 20 articles about digital transformation and reform in public sectors. It was something I did for fun, in my own time, as a way of both recording and sharing my lessons learned from 20 years working at the intersection of tech, government and society (half in the private sector, half in the public sector). I called it the Public Sector Pia Review and I’ve been delighted by how it has been received, with a global audience republishing, sharing, commenting, and most important, starting new discussions about the sort of public sector they want and the sort of public servants they want to be. Below is a deck that has an insight from each of the 20 articles, and links throughout.

This is not just meant to be a series about digital, but rather about the matter of public sector reform in the broadest sense, and I hope it is a useful contribution to better public sectors, not just better public services.

The Pia Review – 20 years in 20 slides

There is also a collated version of the articles in two parts. These compilations are linked below for convenience, and all articles are linked in the references below for context.

- Public-Sector-Pia-Review-Part-1 (6MB PDF) — essays written to provide practical tips, methods, tricks and ideas to help public servants to their best possible work today for the best possible public outcomes; and

- Reimagining government (will link once published) — essays about possible futures, the big existential, systemic or structural challenges and opportunities as I’ve experienced them, paradigm shifts and the urgent need for everyone to reimagine how they best serve the government, the parliament and the people, today and into the future.

A huge thank you to the Mandarin, specifically Harley Dennett, for the support and encouragement to do this, as well as thanks to all the peer reviewers and contributors, and of course my wonderful husband Thomas who peer reviewed several articles, including the trickier ones!

My digital references and links from 2019

Below are a number of useful references for consideration in any digital government strategy, program or project, including some of mine 🙂

General reading

- Some Pia Review articles:

- Apolitical public sectors – The useful benefit of equally serving three masters

- A primer for public engagement – Participatory public governance

- Government as a Platform – the foundations for Digital Government and Gov 2.0

- Trust Infrastructure for the 21st Century

- The myth of IT procurement: how to avoid sprinting off cliffs

- The unintended consequences of New Public Management and how to ensure best public good

- Enabling innovation and collaboration across the public sector

- How to scale impact through innovation and transformation

- How to avoid change for change’s sake

- What does open government mean for digital transformation

- Government 2.0: the substance behind the semantics

- Designing better futures to better inform the present

- The future of service delivery isn’t websites or apps – preparing for personal AIs

- Systemic challenges for digital public sector reform

- Optimistic futures – blog post with predictions by Pia

- Embracing Innovation in Government: Global Trends 2019 – OECD Report

- NSW Gov AI analysis and scan

- Emerging Tech Primers by the NSW Policy Lab: Blockchain, Artificial Intelligence, Rules as Code

Life Journeys as a Strategy

Life Journey programs, whilst largely misunderstood and quite new to government, provide a surprisingly effective way to drive cross agency collaboration, holistic service and system design, prioritisation of investment for best outcomes, and a way to really connect policy, services and human outcomes with all involved on the usual service delivery supply chains in public sectors. Please refer to the following references, noting that New Zealand were the first to really explore this space, and are being rapidly followed by other governments around the world. Also please note the important difference between customer journey mapping (common), customer mapping that spans services but is still limited to a single agency/department (also common), and true life journey mapping which necessarily spans agencies, jurisdictions and even sectors (rare) like having a child, end of life, starting school or becoming an adult.

- Pia Review article that talks about the collaboration benefits of Life Journeys

- A Life Journeys Primer that explains some of the methods and approach (content developed at NSW)

- Birth of a Child life event information from NZ

- The Citizen research work in NZ that kicked off their Life Journey program

Policy transformation

- Transforming Public Policy article (Tim De Sousa and Pia Andrews article)

- A full report on the Policy Lab transformation done in NSW Government

- A useful Harvard article on Agile Policy

Data in Government

- Public Data report from Australian Gov

- Data users and virtualised architecture – resource created by Pia Andrews

- Sharing data is no panacea – Pia Review article on balancing data sharing with verifiable claims and other methods

Designing better futures to transform towards

If you don’t design a future state to work towards, then you end up just designing reactively to current, past or potential issues. This leads to a lack of strategic or cohesive direction in any particular direction, which leads to systemic fragmentation and ultimately system ineffectiveness and cannibalism. A clear direction isn’t just about principles or goals, it needs to be something people can see, connect with, align their work towards to (even if they aren’t in your team), and get enthusiastic about. This is how you create change at scale, when people buy into the agenda, at all levels, and start naturally walking in the same direction regardless of their role. Here are some examples for consideration.

- Designing better futures including links to the Optimistic Futures work

- Preparing for Personal AIs – a future focused approach that is a little more within reach for folk.

Rules as Code

Please find the relevant Rules as Code links below for easy reference.

- Better Rules and Legislation as Code presentation – an explainer presentation deck I did that I keep up to date with new links and references 🙂

- Rules as Code article with Tim De Sousa about the benefits and opportunities

- The first Better Rules Discovery Report from NZ (Nadia Webster) & video by MBIE

- Better Rules Workshop Manual (by Hamish Fraser & Nadia Webster, NZ)

- Rules as Code Handbook (Tim De Sousa) & Better Rules guide (Hamish Fraser)

- The NSW Rules as Code Emerging Tech Primer (the NSW Gov Policy Lab)

- An international Better Rules community forum

Better Rules and RaC examples

- Accident Compensation Act (NZ) Better Rules Discovery Report (ACC)

- Applying Rules as Code for city planning & consenting (Wellington Council)

- NZ SmartStart:https://smartstart.services.govt.nz/ with “financial help” function

- Rapu Ture: NZ Rules Explorer: http://www.rules.nz

- NSW OpenFISCA API code: http://github.com/digitalnsw/openfisca-nsw

- ‘Cereal’ – Active Kids calculator demo: https://digitalnsw.github.io/cereal/

- NSW Rules Explorer: http://nsw-rules.herokuapp.com/

- Openfisca https://fr.openfisca.org/

- “Help Me Plan” concept prototype (2017) that informed subsequent work.

- NZ Rates Rebates Act, the rules as code (calculation, variables) & an easy to use calculator that helps citizens understand how the rules apply to them before applying, noting the same backend RaC tool then supports many tools.

- Mes Aides – a tool for French Citizens to understand the services and taxation implications for their personal circumstances without having to logon.

- The Rules as Code work from the Service Innovation Lab in NZ Govt.

- The Financial Help calculator on the SmartStart (birth of a child life journey) service in NZ.

- Openfisca country packages for reuse & reference, & project documentation.