I don’t have nearly enough time to blog these days, but I am doing a bunch of writing for university. I decided I would publish a selection of the (hopefully) more interesting essays that people might find interesting 🙂 Please note, my academic writing is pretty awful, but hopefully some of the ideas, research and references are useful.

For this essay, I had the most fun in developing my own alternative public policy model at the end of the essay. Would love to hear your thoughts. Enjoy and comments welcome!

Question: Critically assess the accuracy of and relevance to Australian public policy of the Bridgman and Davis policy cycle model.

The public policy cycle developed by Peter Bridgman and Glyn Davis is both relevant to Australian public policy and simultaneously not an accurate representation of developing policy in practice. This essay outlines some of the ways the policy cycle model both assists and distracts from quality policy development in Australia and provides an alternative model as a thought experiment based on the authors policy experience and reflecting on the research conducted around the applicability of Bridgman and Davis’ policy cycle model.

Background

In 1998 Peter Bridgman and Glyn Davis released the first edition of The Australian Policy Handbook, a guide developed to assist public servants to understand and develop sound public policy. The book includes a policy cycle model, developed by Bridgman and Davis, which portrays a number of cyclic logical steps for developing and iteratively improving public policy. This policy model has attracted much analysis, scrutiny, criticism and debate since it was first developed, and it continues to be taught as a useful tool in the kit of any public servant. The fifth edition of the Handbook was the most recent, being released in 2012 which includes Catherine Althaus who joined Bridgman and Davis on the fourth edition in 2007.

The policy cycle model

The policy cycle model presented in the Handbook is below:

The model consists of eight steps in a circle that is meant to encourage an ongoing, cyclic and iterative approach to developing and improving policy over time with the benefit of cumulative inputs and experience. The eight steps of the policy cycle are:

-

Issue identification – a new issue emerges through some mechanism.

-

Policy analysis – research and analysis of the policy problem to establish sufficient information to make decisions about the policy.

-

Policy instrument development – the identification of which instruments of government are appropriate to implement the policy. Could include legislation, programs, regulation, etc.

-

Consultation (which permeates the entire process) – garnering of external and independent expertise and information to inform the policy development.

-

Coordination – once a policy position is prepared it needs to be coordinated through the mechanisms and machinations of government. This could include engagement with the financial, Cabinet and parliamentary processes.

-

Decision – a decision is made by the appropriate person or body, often a Minister or the Cabinet.

-

Implementation – once approved the policy then needs to be implemented.

-

Evaluation – an important process to measure, monitor and evaluate the policy implementation.

In the first instance is it worth reflecting on the stages of the model, which implies the entire policy process is centrally managed and coordinated by the policy makers which is rarely true, and thus gives very little indication of who is involved, where policies originate, external factors and pressures, how policies go from a concept to being acted upon. Even to just develop a position resources must be allocated and the development of a policy is thus prioritised above the development of some other policy competing for resourcing. Bridgman and Davis establish very little in helping the policy practitioner or entrepreneur to understand the broader picture which is vital in the development and successful implementation of a policy.

The policy cycle model is relevant to Australian public policy in two key ways: 1) that it both presents a useful reference model for identifying various potential parts of policy development; and 2) it is instructive for policy entrepreneurs to understand the expectations and approach taken by their peers in the public service, given that the Bridgman and Davis model has been taught to public servants for a number of years. In the first instance the model presents a basic framework that policy makers can use to go about the thinking of and planning for their policy development. In practise, some stages may be skipped, reversed or compressed depending upon the context, or a completely different approach altogether may be taken, but the model gives a starting point in the absence of anything formally imposed.

Bridgman and Davis themselves paint a picture of vast complexity in policy making whilst holding up their model as both an explanatory and prescriptive approach, albeit with some caveats. This is problematic because public policy development almost never follows a cleanly structured process. Many criticisms of the policy cycle model question its accuracy as a descriptive model given it doesn’t map to the experiences of policy makers. This draws into question the relevance of the model as a prescriptive approach as it is too linear and simplistic to represent even a basic policy development process. Dr Cosmo Howard conducted many interviews with senior public servants in Australia and found that the policy cycle model developed by Bridgman and Davis didn’t broadly match the experiences of policy makers. Although they did identify various aspects of the model that did play a part in their policy development work to varying degrees, the model was seen as too linear, too structured, and generally not reflective of the at times quite different approaches from policy to policy (Howard, 2005). The model was however seen as a good starting point to plan and think about individual policy development processes.

Howard also discovered that political engagement changed throughout the process and from policy to policy depending on government priorities, making a consistent approach to policy development quite difficult to articulate. The common need for policy makers to respond to political demands and tight timelines often leads to an inability to follow a structured policy development process resulting in rushed or pre-canned policies that lack due process or public consultation (Howard, 2005). In this way the policy cycle model as presented does not prepare policy-makers in any pragmatic way for the pressures to respond to the realities of policy making in the public service. Colebatch (2005) also criticised the model as having “not much concern to demonstrate that these prescriptions are derived from practice, or that following them will lead to better outcomes”. Fundamentally, Bridgman and Davis don’t present much evidence to support their policy cycle model or to support the notion that implementation of the model will bring about better policy outcomes.

Policy development is often heavily influenced by political players and agendas, which is not captured in the Bridgman and Davis’ policy cycle model. Some policies are effectively handed over to the public service to develop and implement, but often policies have strong political involvement with the outcomes of policy development ultimately given to the respective Minister for consideration, who may also take the policy to Cabinet for final ratification. This means even the most evidence based, logical, widely consulted and highly researched policy position can be overturned entirely at the behest of the government of the day (Howard, 2005) . The policy cycle model does not capture nor prepare public servants for how to manage this process. Arguably, the most important aspects to successful policy entrepreneurship lie outside the policy development cycle entirely, in the mapping and navigation of the treacherous waters of stakeholder and public management, myriad political and other agendas, and other policy areas competing for prioritisation and limited resources.

The changing role of the public in the 21st century is not captured by the policy cycle model. The proliferation of digital information and communications creates new challenges and opportunities for modern policy makers. They must now compete for influence and attention in an ever expanding and contestable market of experts, perspectives and potential policies (Howard, 2005), which is a real challenge for policy makers used to being the single trusted source of knowledge for decision makers. This has moved policy development and influence away from the traditional Machiavellian bureaucratic approach of an internal, specialised, tightly controlled monopoly on advice, towards a more transparent and inclusive though more complex approach to policy making. Although Bridgman and Davis go part of the way to reflecting this post-Machiavellian approach to policy by explicitly including consultation and the role of various external actors in policy making, they still maintain the Machiavellian role of the public servant at the centre of the policy making process.

The model does not clearly articulate the need for public buy-in and communication of the policy throughout the cycle, from development to implementation. There are a number of recent examples of policies that have been developed and implemented well by any traditional public service standards, but the general public have seen as complete failures due to a lack of or negative public narrative around the policies. Key examples include the Building the Education Revolution policy and the insulation scheme. In the case of both, the policy implementation largely met the policy goals and independent analysis showed the policies to be quite successful through quantitative and qualitative assessment. However, both policies were announced very publicly and politically prior to implementation and then had little to no public narrative throughout implementation leaving the the public narrative around both to be determined by media reporting on issues and the Government Opposition who were motivated to undermine the policies. The policy cycle model in focusing on consultation ignores the necessity of a public engagement and communication strategy throughout the entire process.

The Internet also presents significant opportunities for policy makers to get better policy outcomes through public and transparent policy development. The model down not reflect how to strengthen a policy position in an open environment of competing ideas and expertise (aka, the Internet), though it is arguably one of the greatest opportunities to establish evidence-based, peer reviewed policy positions with a broad range of expertise, experience and public buy-in from experts, stakeholders and those who might be affected by a policy. This establishes a public record for consideration by government. A Minister or the Cabinet has the right to deviate from these publicly developed policy recommendations as our democratically elected representatives, but it increases the accountability and transparency of the political decision making regarding policy development, thus improving the likelihood of an evidence-based rather than purely political outcome. History has shown that transparency in decision making tends to improve outcomes as it aligns the motivations of those involved to pursue what they can defend publicly. Currently the lack of transparency at the political end of policy decision making has led to a number of examples where policy makers are asked to rationalise policy decisions rather than investigate the best possible policy approach (Howard, 2005). Within the public service there is a joke about developing policy-based evidence rather than the generally desired public service approach of developing evidence-based policy.

Although there are clearly issues with any policy cycle model in practise due to the myriad factors involved and the at times quite complex landscape of influences, by constantly referencing throughout their book the importance of “good process” to “help create better policy” (Bridgman & Davis, 2012), they both imply their model is a “good process” and subtly encourage a check-box style, formally structured and iterative approach to policy development. The policy cycle in practice becomes impractical and inappropriate for much policy development (Everett, 2003). Essentially, it gives new and inexperienced policy makers a false sense of confidence in a model put forward as descriptive which is at best just a useful point of reference. In a book review of the 5th edition of the Handbook, Kevin Rozzoli supports this by criticising the policy cycle model as being too generic and academic rather than practical, and compares it to the relatively pragmatic policy guide by Eugene Bardach (2012).

Bridgman and Davis do concede that their policy cycle model is not an accurate portrayal of policy practice, calling it “an ideal type from which every reality must curve away” (Bridgman & Davis, 2012). However, they still teach it as a prescriptive and normative model from which policy developers can begin. This unfortunately provides policy developers with an imperfect model that can’t be implemented in practise and little guidance to tell when it is implemented well or how to successfully “curve away”. At best, the model establishes some useful ideas that policy makers should consider, but as a normative model, it rapidly loses traction as every implementation of the model inevitably will “curve away”.

The model also embeds in the minds of public servants some subtle assumptions about policy development that are questionable such as: the role of the public service as a source of policy; the idea that good policy will be naturally adopted; a simplistic view of implementation when that is arguably the most tricky aspect of policy-making; a top down approach to policy that doesn’t explicitly engage or value input from administrators, implementers or stakeholders throughout the entire process; and very little assistance including no framework in the model for the process of healthy termination or finalisation of policies. Bridgman and Davis effectively promote the virtues of a centralised policy approach whereby the public service controls the process, inputs and outputs of public policy development. However, this perspective is somewhat self serving according to Colebatch, as it supports a central agency agenda approach. The model reinforces a perspective that policy makers control the process and consult where necessary as opposed to being just part of a necessarily diverse ecosystem where they must engage with experts, implementers, the political agenda, the general public and more to create robust policy positions that might be adopted and successfully implemented. The model and handbook as a whole reinforce the somewhat dated and Machiavellian idea of policy making as a standalone profession, with policy makers the trusted source of policies. Although Bridgman and Davis emphasise that consultation should happen throughout the process, modern policy development requires ongoing input and indeed co-design from independent experts, policy implementers and those affected by the policy. This is implied but the model offers no pragmatic way to do policy engagement in this way. Without these three perspectives built into any policy proposal, the outcomes are unlikely to be informed, pragmatic, measurable, implementable or easily accepted by the target communities.

The final problem with the Bridgman and Davis public policy development model is that by focusing so completely on the policy development process and not looking at implementation nor in considering the engagement of policy implementers in the policy development process, the policy is unlikely to be pragmatic or take implementation opportunities and issues into account. Basically, the policy cycle model encourages policy makers to focus on a policy itself, iterative and cyclic though it may be, as an outcome rather than practical outcomes that support the policy goals. The means is mistaken for the ends. This approach artificially delineates policy development from implementation and the motivations of those involved in each are not necessarily aligned.

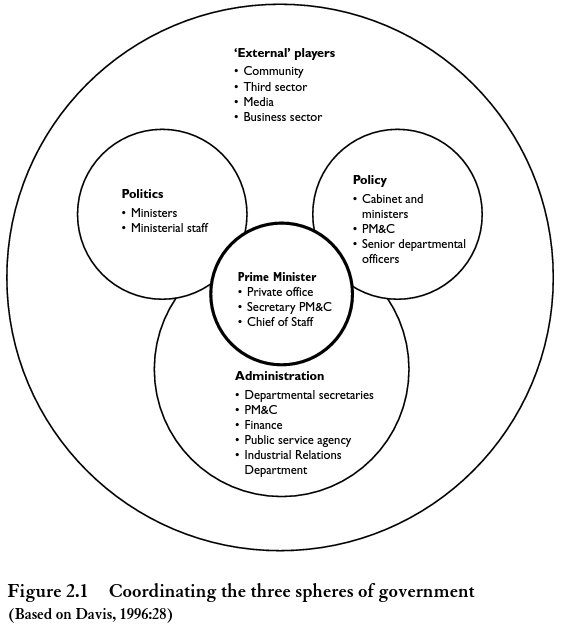

The context of the model in the handbook is also somewhat misleading which affects the accuracy and relevance of the model. The book over simplifies the roles of various actors in policy development, placing policy responsibility clearly in the domain of Cabinet, Ministers, the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet and senior departmental officers (Bridgman and Davis, 2012 Figure 2.1). Arguably, this conflicts with the supposed point of the book to support even quite junior or inexperienced public servants throughout a government administration to develop policy. It does not match reality in practise thus confusing students at best or establishing misplaced confidence in outcomes derived from policies developed according to the Handbook at worst.

An alternative model

Part of the reason the Bridgman and Davis policy cycle model has had such traction is because it was created in the absence of much in the way of pragmatic advice to policy makers and thus has been useful at filling a need, regardless as to how effective is has been in doing so. The authors have however, not significantly revisited the model since it was developed in 1998. This would be quite useful given new technologies have established both new mechanisms for public engagement and new public expectations to co-develop or at least have a say about the policies that shape their lives.

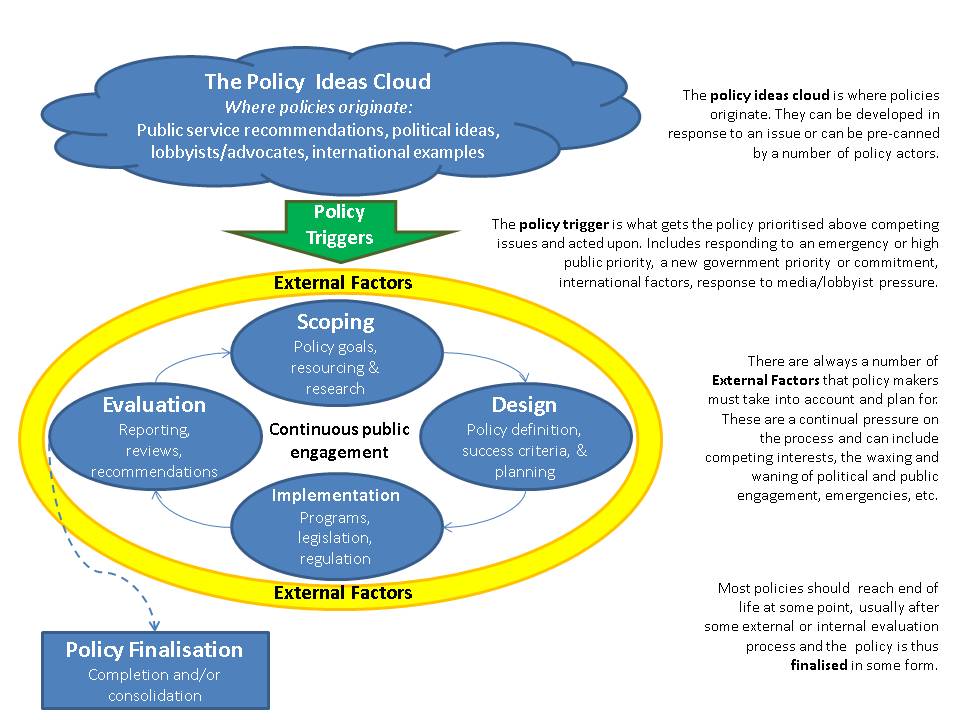

From my own experience, policy entrepreneurship in modern Australia requires a highly pragmatic approach that takes into account the various new technologies, influences, motivations, agendas, competing interests, external factors and policy actors involved. This means researching in the first instance the landscape and then shaping the policy development process accordingly to maximise the quality and potential adoptability of the policy position developed. As a bit of a thought experiment, below is my attempt at a more usefully descriptive and thus potentially more useful prescriptive policy model. I have included the main aspects involved in policy development, but have included a number of additional factors that might be useful to policy makers and policy entrepreneurs looking to successfully develop and implement new and iterative policies.

It is also important to identify the inherent motivations of the various actors involved in the pursuit, development of and implementation of a policy. In this way it is possible to align motivations with policy goals or vice versa to get the best and most sustainable policy outcomes. Where these motivations conflict or leave gaps in achieving the policy goals, it is unlikely a policy will be successfully implemented or sustainable in the medium to long term. This process of proactively identifying motivations and effectively dealing with them is missing from the policy cycle model.

Conclusion

The Bridgman and Davis policy cycle model is demonstrably inaccurate and yet is held up by its authors as a reasonable descriptive and prescriptive normative approach to policy development. Evidence is lacking for both the model accuracy and any tangible benefits in applying the model to a policy development process and research into policy development across the public service continually deviates from and often directly contradicts the model. Although Bridgman and Davis concede policy development in practise will deviate from their model, there is very little useful guidance as to how to implement or deviate from the model effectively. The model is also inaccurate in that is overly simplifies policy development, leaving policy practitioners to learn for themselves about external factors, the various policy actors involved throughout the process, the changing nature of public and political expectations and myriad other realities that affect modern policy development and implementation in the Australian public service.

Regardless of the policy cycle model inaccuracy, it has existed and been taught for nearly sixteen years. It has shaped the perspectives and processes of countless public servants and thus is relevant in the Australian public service in so far as it has been used as a normative model or starting point for countless policy developments and provides a common understanding and lexicon for engaging with these policy makers.

The model is therefore both inaccurate and relevant to policy entrepreneurs in the Australian public service today. I believe a review and rewrite of the model would greatly improve the advice and guidance available for policy makers and policy entrepreneurs within the Australian public service and beyond.

References

(Please note, as is the usual case with academic references, most of these are not publicly freely available at all. Sorry. It is an ongoing bug bear of mine and many others).

Althaus, C, Bridgman, P and Davis, G. 2012, The Australian Policy Handbook. Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 5th ed.

Bridgman, P and Davis, G. 2004, The Australian Policy Handbook. Sydney, Allen and Unwin, 3rd ed.

Bardach, E. 2012, A practical guide for policy analysis: the eightfold path to more effective problem solving, 4th Edition. New York. Chatham House Publishers.

Everett, S. 2003, The Policy Cycle: Democratic Process or Rational Paradigm Revisited?, The Australian Journal of Public Administration, 62(2) 65-70

Howard, C. 2005, The Policy Cycle: a Model of Post-Machiavellian Policy Making?, The Australian Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 64, No. 3, pp3-13.

Rozzoli, K. 2013, Book Review of The Australian Policy Handbook: Fifth Edition., Australasian Parliamentary Review, Autumn 2013, Vol 28, No. 1.