In government we often speak about policy levers, but in the real world, a lever without a fulcrum is just a plank of wood. Levers are needed to lift a load, but without a fulcrum, you can’t move it very far. Fulcrums are needed to dramatically increase the impact of a lever without having to increase the effort/resource. Basically, levers without fulcrums are pretty ineffective.

Sometimes even ambitious change agendas can unintentionally adopt a levers-without-fulcrums pattern. For instance, setting up a team to innovate without normalising a culture of innovation across the organisation. Hiring or training extraordinary talent and then not letting them make any decisions or bring ideas to the table. Training staff on public engagement without creating an appetite for public input. Every lever needs a fulcrum.

Once you look for it, you can see this pattern everywhere.

So below are five of my favourite fulcrums to complement the usual policy levers you have today 😊 These are all tried and tested in various governments. These fulcrums are: teaching public sector craft to all who work in (and with) the public sector, a responsible implementation mindset, servant leadership, structuring around outcomes, and finally the critical fulcrum of raised expectations.

Fulcrum 1: Teaching public service craft to all involved

All public servants used to be trained in public service craft. At some point, about 30 years ago, there was a change that mechanised the public sector (driven by New Public Management) and started bringing people in for a particular skillset (developer, accountant, lawyer, project manager, etc) with limited training on the context in which they’d be applying those skills. These days, generally only policy people are expected to be ‘trained’ in the ways of government, and even then, many public policy courses teach only the mechanics of public sector without the responsibilities or clear delineation of powers and accountabilities.

We have seen the results of this in shocking testimony throughout the Robodebt Royal Commission, as senior public servants demonstrated a complete misunderstanding (and sometimes abdication) of their responsibility to be trusted stewards acting both lawfully and in the best public interest, instead believing their job to just advise, and then loyally (blindly?) implement the decisions of the government of the day, whatever the cost, conflict, impact or legality. This culture issue is well articulated in the recent submission to the Robodebt Royal Commission by the UNSW Allens Hub and Australasian Society for Computers and the Law.

Similarly, political staffers need to be trained on the responsibilities, dignity and accountabilities of being in office (whether in Government or Opposition), and should be taught what a healthy relationship between Ministerial offices and departments looks like, as has been well articulated in Professor Andrew Podger’s well written recent analysis.

The reason public sector craft should be taught to all public servants, at all levels, is to ensure that everyone knows what good, responsible, ethical and lawful governance looks like, and is able to identify and hold the line when required. This ensures that good and high integrity governance weathers the storms of political change, while being capable of maintaining the trust and confidence of the Government, the Parliament and the People, because there is significant benefit in equally serving all three masters.

Fulcrum 2: A “responsible implementation” mindset

“Frank advice, fearless stewardship, responsible implementation”

There is a LOT of decision making to be made that doesn’t require Ministerial approval, where public servants at all levels can and should confidently exercise their delegations in accordance with the mandate and legislation.

Personally, I would like to change the old saying from “frank and fearless advice” to “frank advice, fearless stewardship, responsible implementation”, to help public servants, particularly policy folk, to realise the job is more than an advisory one. Stewardship is being added to the APS Values and will help ensure a more sustainable and public good mindset across the senior executive. Implementation is always where impact is felt, so responsible implementation is frankly more critical than good advice. Fearlessness should be about how the sector is maintaining its balance, integrity and trustworthiness in the face of adversity, influence and power.

In any case, the Government of the day generally only tweaks a small proportion of the whole mandate of the public sector, but public servants are expected to lawfully and responsibly administer all their obligations, not just the policy agenda of the Government of the day. Ministers (and Governments) can and do set “Big P” Policy, but where that policy conflicts with the law, legislation, constitution or frankly, with public benefit, then public servants have a responsibility to say no, not to just offer more advice but implement anyway.

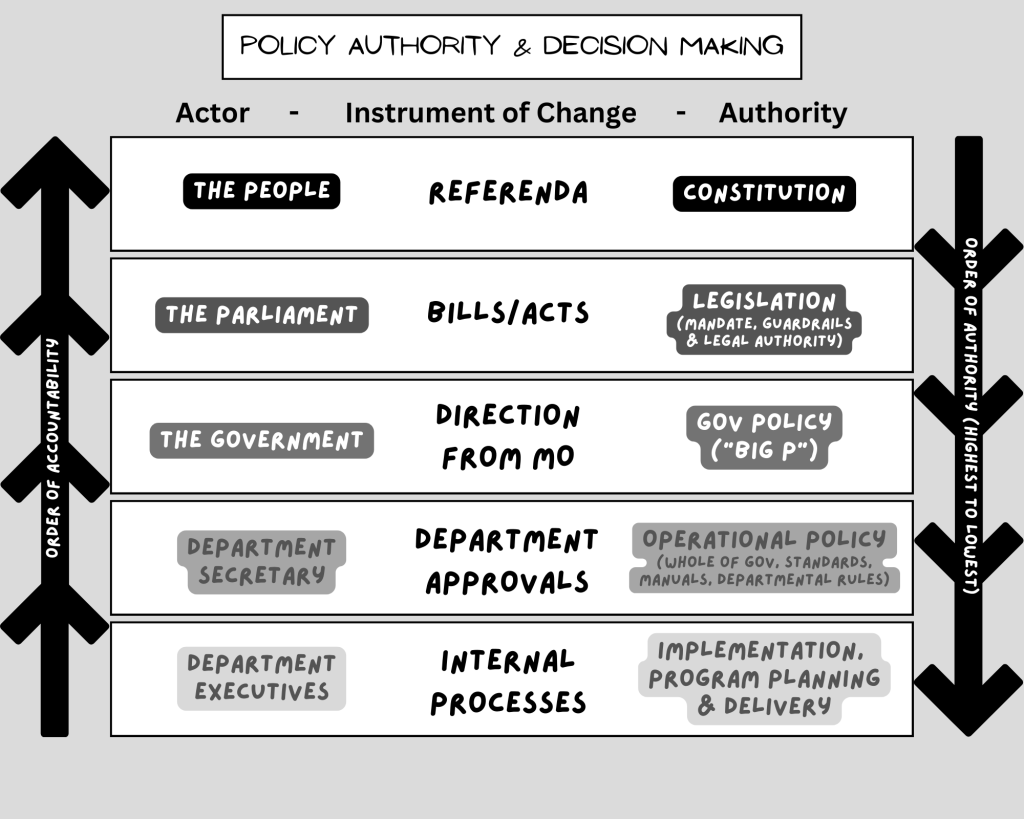

The lack of training from fulcrum 1 has led to a situation where many public servants and ministerial staffers don’t know how they should interact. For instance, Ministers should ideally identify outcomes they wish to achieve, and ask departments to provide analysis and options, but Minister’s generally shouldn’t dictate solutions or delivery. Departments have a whole mandate to deliver outside of the Minister’s objectives, found in the legislative and constitutional foundations of the portfolio. Below is a little diagram I made to help folk understand where authorities lie and the actors and change mechanisms required for each. For example, there is significant authority and decision making around the operational policies and program implementation in the department itself, which doesn’t require continual Ministerial approvals.

If more public servants used their full delegation to genuinely, openly and confidently serve the public, and refer continually to the mandate laid out in constitution and legislation, we would have better governance, improved public trust and dramatically better public outcomes.

Fulcrum 3: Servant Leadership

When I started working in the NSW Government as a senior executive, my new team asked me on my first day what my success criteria for them was. I thought for a moment, and answered: 1) that was have a measurably beneficial impact for the people/communities we serve; 2) that we are looked to and considered exemplars for how we work, not just what we deliver; and 3) that everyone in the team has joy every day at work. I truly believe that people should leave every workplace better than when they started.

Joy is a wonderful indicator for when people feel heard, empowered, working on meaningful stuff and valued. It shows people are busy but not burned out, delivering value and getting the balance roughly right. In the public sector where many people are driven by a deep desire to do good, joy is enabled by embracing and supporting that desire, and helping people bring their whole creative and brilliant selves to the job. An empowered and joyful team is a force of nature. So why are so many teams not joyful?

It is no secret that public sector leadership in recent decades has slowly devolved into a murky soup of micromanagement, distrust and politicisation. This is not because we have magically attracted such individuals pre-formed, but rather because we have normalised an executive environment with training and incentives that drives and rewards these behaviours. When a leader, at any level (team, branch, division, department) see their job as “managing” people, there is an inherently disrespectful and toxic presumption that people are not willing or capable of managing themselves. “Managing” people quickly leads to micromanaging people, leading to a very real sense of helplessness and disempowerment across the service.

People rising through the ranks have also been taught that “expertise” is a dirty word, and to really get anywhere you should become a “generalist”. This has led to an unhealthy and internalised disregard of internal experts, and mutual incomprehension between decision makers and those with the experience and expertise needed to inform decisions.

Equally problematic is the lack of public sector leadership development. Executives are often promoted or recruited through being highly capable at doing, but are not then taught how to empower others. Many courses teach execs to distrust their staff, to allocate tasks rather than outcomes, to focus on efficiency rather than public or policy outcomes, and to reward compliance over creativity.

There are solutions though. I have seen and adopted ”Servant Leadership” as a powerful and effective fulcrum to shift and improve leadership culture in many public sectors around the world. It provides both a mindset/cultural shift and a method for building high performing teams capable of delivering real impact. Servant leadership reframes “leadership” as the act of empowering and supporting people to succeed, growing the confidence of staff and improving their capability and confidence to deliver.

Product management, done well, provides a good test for Servant Leaders. A senior program or project owner needs to be able to delegate decision making to product owners and managers, and to oversee and guide rather than direct. When product teams lose (or never truly gain) delegation of decision making, they are unable to design, deliver, manage, continuously improve or pivot products in response to changing needs or policy.

Servant leadership creates an active practice of listening, enabling and encouraging all staff to bring their best selves, creating the possibility of high performing and sustainable teams that can work smarter across disciplines, and can innovate and engage. Servant leadership actively delegates down, supporting staff to own outcomes along with relevant decision making to be at the right level, a critical requirement for better policy and service delivery outcomes.

Fulcrum 4: Structuring around outcomes

Whilst ever public servants have to provide a cost centre just to talk to each other (let alone work together), we will continue to see structural segmentation of disciplines, and a structural inability to be outcomes driven. There are small ways to structure around outcomes, even within highly segmented structures, like funding an outcome under one cost centre, and bringing together all the capabilities required for that outcome (rather than begging, borrowing, seconding, stealing or journaling), and building different disciplines and capability uplift into your project and programme budgets (such as 0.2 FTE from policy, or secondees from the frontline, or funding for service design that includes training for internal staff to learn for next time).

Whenever I build a government program, I ensure we identify and budget for the minimum viable set of capabilities to deliver the outcome end to end. We can always supplement with collaborations, vendors, partnerships, etc, but without the minimum viable capabilities represented in the team, then any delivery is always subject to the whims and pressures of someone else’s urgency laden prioritisation queue. We need to fund services for continuous improvement, rather than funding a launch. We need to fund end to end policy management, rather than blindfolded baton passing between different functions or departments. We need structures (and cost centres) that ensure full accountability for an outcome is supported by funding and multi-disciplinary capabilities to deliver the outcome.

Fulcrum 5: Raised expectations

The final fulcrum sounds simple, but is really the most important. Once of the most difficult to shift and self-fulfilling aspects of learned helplessness is when people allow themselves to continually expect the worst. Cynicism creates a form of acceptance and permission for poor behaviour and poor performance to continue, especially in the senior ranks.

When I entered the public sector over a decade ago, I had already seen this pattern from the outside, and I promised to never allow myself to not be surprised at things that make no sense. I ask questions, validate assumptions, look at actual versus intended impact and I encourage people to think about and aim for what will best serve the community, not to just tick the box. When I express surprise at something, people often say to me “but you’ve worked in government a while, surely you’ve seen this before”. I cheerfully tell them I made a conscious choice to not grow numb to systemic issues, often leading to great discussions about to redirect the energy of surprise and frustration into fixing the system, and the dangers of unintentionally propping up bad systems through low expectations.

So a critical but difficult fulcrum for genuine change needs and must be for all public servants to raise our expectations, at all levels. Expect more from yourself, your peers, your bosses, your department, your senior leadership, your Secretary. Don’t praise someone for being kind when that is a basic decency you should expect from everyone. Don’t be satisfied with an executive just listening to your ideas, unless they also give you agency to implement them. Have you noticed that our expectations of people seem to diminish the further up the hierarchy people climb? We should have the highest expectations of our most senior public servants. They should exemplify the very best stewardship, commitment to public good, integrity, culture, responsible administration and equally serving the Government, the Parliament and the People.

Raise your expectations, keep them high, and always, always, expect the best from people. You’d be surprised how many rise to that expectation 😊 You’ll be surprised how powerful a fulcrum it can be.

Over to you

These are five of my favourite fulcrums, what are yours? How have you already applied similar approaches in your own department? What does better public sector administration look like for you? Let’s get some sharing so we can create a better service together, and so that our policy, programme and other levers are more than planks.