TL;DR: An overview of my insights from FWD50 2022, including the talk I gave, and the responses to the questions submitted to my talk 🙂 In short, it was awesome! Apologies for the long post!

Every year I attend (or participate in) FWD50, a Canadian conference that I consider the world’s best government transformation event. It is such a special conference because it purposefully doesn’t specialise in just one domain (like the plethora or data, digital, procurement or other events I normally see), but rather it brings together all disciplines around burning questions of the day, and how might the public sector become fundamentally better for the people and communities it serves. FWD50 manages to simultaneously be a social platform for public servants to connect, evolve and be brave together, as well as being something of a petri dish where everyone can participate in co-creating a fundamentally more humane approach to public service. The participants are highly diverse in all respects, with over a hundred government jurisdictions represented from around the world, and thought leadership exhibited from up and down the usual hierarchy chain, embracing the expertise and experience that we all have to share. Some of the most mindblowing sessions often come from junior public servants 🙂

FWD50 is the brainchild of the Croll siblings, Alistair and Rebecca, with a small army of conference experts and public servant volunteers. I can’t recommend this event enough, and the leadership the Crolls have shown, not just in what they’ve built, but in how they continue to deliver it through kind, inclusive, collegial and respectful sharing and provocations. They and their army of awesomeness have also managed to grow and evolve through the pandemic, simultaneously running an in person AND online event, drawing from all the lessons of the last few years, and delivering something both excellent and exemplary for organisations trying to work through their post-COVID existential crisis 🙂

It was also an opportunity for me to connect with colleagues and friends in the Canadian Government, including my old DECD (Digital Experience and Client Data) team at Service Canada. It was SUCH a delight, such a joy, to meet, hug, and hear about how the team are going, including Aaron Jaffrey, who took over leading DECD. I could not have asked for a better person to take care of this very special team, thanks again Aaron! DECD continue to design and deliver amazing things, to be an exemplar for purpose-led, kind and calm culture, and to truly put people at the centre of the design. I miss you all and continue to be your biggest fan 🙂

Below are a few take aways and lessons from the event, shared in the hope they will be helpful, and to encourage more folk to tune in to the discussions and content from FWD50 as a provocation to help plan holistic government transformation in all your own teams 🙂

Key insights

- I LOVED Alistair’s talk on the second day, where he reminded us that we are using a system of government that is hundreds of years old, and that the next generational shift in “government” is likely in the process of happening, and we won’t even be able to recognise it. He used the Gutenberg Press as an example of how enormous a change we are living through with the Internet, and it was great to go so big and ambitious in thinking, while we set new horizons.

- Openness and working openly remains the most commonly proposed strategy for building trust, designing and delivering better policy/services, continuous improvement, public engagement, and for genuinely responsible government in the 21st century.

- Energy is not something you get from someone else. It is something you co-create. I’ve had a few people say my talk energised them, but actually, the energy was a result of us all participating enthusiastically in the topic 🙂 When you think someone else energises you, you are potentially missing the vital role you play in the equation 🙂

- If we don’t solidify the gains made throughout COVID, then we’ll lose ground, which may in fact lead to losing a large chunk of the workforce who could leave in frustration. People will simply leave if we don’t normalise and support gains like flexible working, greater transparency/openness of work, improved trust and delegation further down the hierarchy, inclusive and geographically diverse hiring, virtual teams, and more streamlined and rapid delivery of services to the general public.

- Change has never succeeded as a top down strategy. True change requires an approach that invites all staff into the process of designing a meaningful and purpose based future state, identifying how they can each work towards it, and supporting/trusting them to be a part of it. Frontline and SMEs in gov want to see positive change, they just don’t want change for the sake of change, which might in turn negatively impact their clients and the communities they serve.

COVID changed our minds, but not yet our systems

I was surprised by the enormous gap I observed between senior executives and the broader community of public servants, a gap so large it had an almost tangible weight. I’ve always believed change can only happen when you first change your mind. For most public servants, COVID has fundamentally changed our minds. The pandemic irrefutably proved that our systems, structures, processes and ways of working are not capable of responding effectively or humanely to the speed of change/need in the modern world. Sure, we can leverage all kinds of emergency superpowers to push things through in weeks/months instead of years, but we always revert to “normal” after the emergency, and in any case, the more pressure there is, the more insular we become in how we operate.

We have entered a time of continuous emergencies, and most public servants intuitively know that we need to fundamentally rethink how we do public administration and governance in a mission, purpose and values oriented way. Though many of the talks at FWD50 touched upon the changed world since COVID (check out the agenda here), they seemed to fall into three broad patterns: disruptive reform, building public trust, and what I’ll cheekily call “Hello 2019”.

We heard incredible stories of disruptive reform in Ukraine, US Veteran Affairs, the importance of a “moonshot” mindset from X, policy transformation, and what “winning” could look like if we be more purpose and outcomes driven. We heard about efforts and models to improve public trust and confidence, to identify and meeting public expectations (beyond a “customer” imperative), how to design for legitimacy, to value and engage employees in a transformation agenda, how to govern AI, and the need to consider the undeniable (but usually overlooked) relationship between the quality of government services and public trust.

But we also heard several “Hello 2019” talks that would have been completely great 3 years ago, but felt just a little out of touch with the heightened expectations and new challenges from almost 3 years of COVID. The talks about “we just need some better platforms”, or “policy should just focus on delivery”, or “it all starts with digital identity”. It’s not to say these aren’t important topics to explore, but it felt almost like there is a new gravity in place, where most public servants and the people we serve want us to urgently focus on the why, not just the what or how. In the grand scheme of things, it is easy to deliver new digital stuff, but public sectors need to create the ways and means for people to thrive in ambiguity, to navigate complexity, to be socially included and supported when things go wrong, and to live well, even through rolling crises. If public institutions can’t deliver values based and meaningful public good, and do so in alignment with public values and expectations, then tech, tools, platforms, design and other mechanisms for “how” will continue to distract us from delivering on our purpose.

I feel like for all the trauma we have experienced over the last few years, COVID has acted as a form of necessary intervention on several fronts:

- A personal intervention, as we all reconnected with family and friends, supported each other through loss and fear, realised how much work had taken over our lives.

- A work intervention, as we realised how thin and unnecessary so many things are that usually get in the way of delivering great public services and policy outcomes. We empowered people at all levels to work (micromanagers really struggled with remote teams), we worked more transparently, we really focused on the urgent needs in our communities, and we streamlined a lot of bureaucracy as we reached out a discovered we could, in fact, collaborate and deliver together, and focus on real human needs and outcomes.

- A human intervention, as we all had a genuinely shared experience with all other people around the world, regardless of where we are from or who we are. This has provided a sense of empathy with each other, something we might choose to maintain, so we can see more what we have in common with each other moving forward.

So when I see talks that basically feel like “Hello 2019”, it feels like either a missed opportunity, or perhaps like the speaker is slightly out of step with the changed environment they occupy, which is a real pity.

I suggest it is imperative that we all work diligently to change the systems we work within to reflect the change we have had in our minds, rather than allowing our minds to be reverted to the old world. This is not something to wait for others to do, or to “hope” for. Just get on with it, and be the change you want to see 🙂

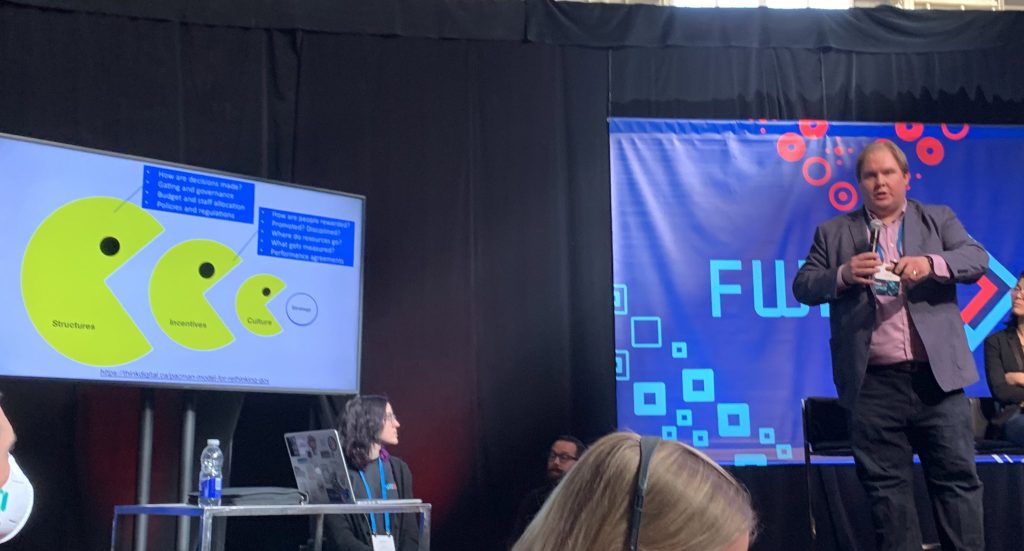

Structure eats Incentives eats Culture eats Strategy, for breakfast!

This workshop was just excellent, and one of my favourites this year. It was run by the Think Digital and Code for Canada crews with a few public servant volunteers. They invited participants to share barriers, using an expanded version of the old “Culture eats Strategy for Breakfast” idea. Their proposal was that Incentives eat Culture, and Structure eats Incentives, both of which I have certainly observed in my time working in and with public sectors. I thought it was a profound sentiment and one worth considering in any program or project. Often we get caught up with the issues created by fixing behaviours through better culture, or the lack of a “light on the hill” that strategy is supposed to provide, but both can be undermined or perverted by incentives and structure. For example, an efficiency agenda will always incentivise saving money for the sake of saving money, which always kills opportunities to deliver genuine or purpose driven public good, let alone new value to the public.

Similarly, the current structure of most government departments was adopted during the NPM (New Public Management) years. It created functional segmentation of disciplines, which has led to a structural barrier to being outcomes focused. Basically, your policy people don’t walk to data, don’t talk to tech, don’t talk to program, etc etc. Collaboration is only possible with a hard won and years in the making cost centre, and cross functional engagement happens at the 11th hour (if at all) rather than from the first minute. Structures shape incentives by the function of your team, and this is most obvious when you talk to IT Departments who have been largely asked to just be efficient for the sake of efficiency, creating a huge barrier between those doing, and the policy or mandate outcomes that their department is responsible for.

This framing was VERY helpful, and I’m thankful to Ryan, Dorothy, Winter and Luke for the wonderful session 🙂

My talk: building for legitimacy in government

My main talk this year focused on how to build trustworthy systems in the special context of government (slides here). I started by talking about why trust is critical for public sectors, and how trust is earned, not asked for. Public trust and confidence in public institutions is a necessary foundation for all that we administer and deliver in their name. Without trust, public sectors and governments everywhere run the risk of losing perceived and then actual legitimacy, leading to instability and chaos. I then talked about the key ingredients for trust: operating in good faith, with integrity, and as expected by the people/person we deal with. Good faith can be demonstrated in the public sector through a systemic and measurable commitment to human-centred and humane outcomes, strong governance. High integrity of gov can be demonstrated by operating in a way that is demonstrably lawful, accurate, high veracity, assured, consistently applied and appealable. Meeting public expectations of gov means reflecting public expectations, values and needs, doing no harm, being transparent and operating within relevant legal, social, moral and jurisdictional limitations of power.

I then used three use cases to apply this approach:

- The use of AI in public sectors, specifically the risky and difficult domain of Machine Learning (ML) based Automated Decision Making (ADM) systems. I laid out how although ML/AI can of course be very helpful in mary use cases, when it comes to ML based ADM, we lose both traceability to legal authorities (legislation, regulation, etc and explainability as required under Administrative Law) and we lose consistency of implementation (which conflicts with Rule of Law, as the system starts to get different outputs to common inputs over time as it “learns”). I presented a series of ways to identify and mitigate harm, but basically made the case that ADM systems in government that are subject to Administrative Law should most likely be rules based, not machine learning based.

- For government services, I spoke about key epics that a product team might include that would help services comply to the special context of government, such as recording and providing an explanation of service decisions, ways to measure and monitor for human impact (not just fiscal success indicators), ways to draw on representative and diverse knowledge systems in the design and governance of services, and how truly humane services require human centred futures, measures and design.

- For trustworthy operating models, public institutions need to establish humane work environments, empowered teams, a safe and high integrity culture, where anyone can speak truth to power, with all staff having the respect, capacity and support to think and act in the best interests of the public, not just working at 100% capacity on the most urgent thing all the time. This requires a systemic shift to servant leadership inside institutions, but also a strategic commitment to participatory governance, where the public can participate in and help ensure truly humane policies and services.

My final thought was we need a few additional tools in our toolbox to realise the vision and value of truly trustworthy and legitimate public services in the 21st century:

- Clarity on purpose for a policy or service – if you don’t know the intended impact, how do you know it is working as hoped? We shouldn’t build for the sake of building, we need to design and build for a purpose.

- Legislation/regulation as code – to test against, build upon, model with, explore and to help people engage with their rights & policy development in a more interactive and meaningful way.

- Algorithmic/models transparency – to raise public confidence, but also to enable independent testing, research and policy proposals, especially from the academic sector and community advocates.

- Tiered risk approach (eg the Canadian Algorithmic Impact Assessment + categories of use) – to avoid the one approach to rule them all approach, and to align risk to how AI (and other systems) are used and their impact, rather than just intrinsic generalist risk.

- Design for proactive explanation – this requires traceability to legislation/regulation (as code) and to case law/exceptions, it requires records keeping for decisions, and better communications to the public.

- Participatory policy and governance

- A human impact measurement framework, to complement fiscal measures

- Real time monitoring & escalation mechanisms, that feed back into continuous service improvement, and critically, continuous policy improvement. Also to escalate patterns of harm that are detected as they emerge.

The questions submitted for my talk are below with answers 🙂

- Where is the balance between meeting our expectations within ourselves and the parameters in which we are sometimes required to work? How do effectively manage expectations for the public?

Honestly I have found that being as open as possible helps build trust to best navigate those waters. We should be open about that balance, as much as we can be, and people don’t expect everything they say to be unthinkingly implemented, but they do expect to be heard. So open up channels for regular communication, for relationship building, for trust building, and you’ll get better policy, better services, better governance, and you’ll get more trust to deal with the things you can’t be as open about. Here is a blog post I wrote about balancing the three masters we all serve: the Government of the day, the Parliament, and the People 🙂

- How do you separate trust in the public service, ie Government and politicians?

By being politically neutral and having a voice for the public sector. People will always be wary of politics, but they should be able to trust their public institutions. So have a voice, demonstrate your commitment and stewardship of the best public good, and maintain that healthy separation of politics and public sector. In Canada you have that lovely bridge demonstrating the division of power. Do your part to always do the right thing, not what’s politically expedient. And ensure you talk about the work of your department directly to the public. If you are only communicating through the lens of political speeches or media releases, you will likely have a problem 🙂

- Should there be more accountability for companies to level the playing field of trust, since (some) lack of trust comes from governments’ openness, which exposes all its beautiful disfunctions?

I think it is entirely reasonable for governments to ensure how they interact with companies includes requirements of openness and accountability. But it is hard to regulate behaviours in companies, some will be open by default, some won’t. But you can make certain things a requirement of contracts with companies that can at least ensure the ones who you work directly with meet the requirements of good government, good accountability, and meet the public trust test. But as above, the best way the public sector can grow trust is to have a voice of it’s own. People assume the worst of the public sector because a) it’s everyone’s favourite punching bag, and b) it has unmatched power in a society so people should have some distrust. The onus on the public sector to earn trust is higher than on companies, which is as it should be. So earn that trust by being trustworthy, rather than needing to expose the disfunction of others around us 🙂 All organisations have disfunction, and we can all learn from each other, but have confidence in our value to society.

- What is the first human impact measure to start with?

Great question! Honestly just starting is good, but if you ask citizens what they think, then whatever you choose will be reflective of their hopes and fears. It doesn’t need to be the best one, just start. If your jurisdiction is struggling with homelessness, make that your first measure. Similarly for employment, or health indicators, or perhaps trust in government? 🙂 This “Trust in Australian Public Services” report provides a good blueprint for baselining and monitoring changes in public trust over time.

- How do we build trust with groups who actively seek to see us fail?

Like whom? If you are talking about nefarious actors or people who want the public sector to fail, then clearly they aren’t operating in good faith, so demonstrate your value and build trust with the people and communities who actually need to trust you 🙂 - Can you also talk how the “reputation” of a governing system is impacted by changes in trust?

When people lose trust in the public sector, everything we administer is at risk of losing perceived legitimacy. It is as serious as that. Trust is critical for public sectors to operate with legitimacy. - How do we shift how executives see AI & try to incorporate tiny improvements to make the backend better?

Present a vision for what good could look like to get buy in, and then show how all the different ingredients needed make the cake (including the impact if you skip an ingredient!) - You show a sensitivity to indigenous people. How can we use assisted decision making to increase indigenous peoples trust in government?

Ask them 🙂 Involve them in the design, delivery and oversight of such systems. Isn’t isn’t just about understanding user needs, it is about including different perspectives in the decision making and governance. - How do you feel about ADM responsibility certification initiatives?

I can’t answer that as a generic question, because each initiative has strengths and weaknesses. I think it is critical that people realise that an ADM system of any kind is still subject to all the other accountabilities and responsibilities we have in gov, so they should be certified against that rather than yet another certificate that a person can tick which may or may not meet the robust requirements of Administrative Law. Most frameworks for AI I’ve seen only suggest, at the heart of it, two things: human in the loop, and consideration of some nice sounding principles. Both these mechanisms can be helpful but are so far from sufficient it is deeply concerning to see them help up as the baseline. The AIA at least provides a risk framework to scale up and down controls based on impact. I believe we need to be able to demonstrate at a minimum, the explainability with traceability to the legal authorities of the public institution for all gov ADM systems, which arguably requires 1) legislation/regulation as code to trace to. But I also think we need 2) human impact measurement and monitoring (to detect and mitigate harm), a 3) clear goal/outcome for all policies with a “test suite” for each that articulates what output should come from what inputs in a variety of scenarios to test against, and 4) a clarity of what type of AI should be used for what types of activities in gov. ML for research, patterns analysis, investigations, etc can be great (if you can tackle the bias in the data issues). - In example 3, what do you mean by strong culture? Can you give an example?

Culture informs behaviours. If you don’t have a strong culture that values expertise, that prioritises public good, that operates with integrity and independence, etc, then behaviours can sneak in that undermine the legitimacy of the sector. All public servants, no matter their job or level, need to operate with integrity and in the best public interest. When people are encouraged to just do the job and not contribute “above their pay level” then we lose integrity, we lose all the feedback loops that would otherwise support best public outcomes. - What do you do when youre entire organization thinks differently than you when it comes to trust?

Hmm, hard one! Well, if it was me (and it has been) then I would make the case, show the impact of low trust, propose what good looks like and how high trust supports the mandate and goals of the org, I would take every opportunity to demonstrate what high trust looks like, and if all else fails, I would seek a different public sector employer. - How do separate trust in public servants from the large companies that work for us with a profit motive?

By being loud and proud public servants 🙂 - What are 3 concrete things individual public servants can do to support legitimacy of government services?

1) Take every opportunities to engage with communities, advocacy orgs and civil society orgs in your work, they don’t have to be formal comms exercises 🙂 2) always ask the hard questions: how will this benefit the public? how will we know if it is creating harm? Use my questions from the talk as epics in yoru product/policy backlog 🙂 and 3) Take just a little time to imagine what good looks like, to connect with others who are similarly values-driven, and to always, in everything you do, try to bring about something better for people. This last one sounds fluffy, but you’d be surprised how much it influences every concrete action, plan, decision etc in your life. - Thinking back on yesterday’s intro, do we think the digital era may eventually usher in a new participatory democracy?

Yes. I think it already is doing so, and the change in people’s expectations of government is just the start. We didn’t see a global wave of democratic systems of government until there was a critical mass of people expecting to be able to vote for their leaders rather than to just inherit them. Expectations change the world, and people today expect to have some say in how government operates, not just who they elect in the Parliament. - How do you ensure participatory governance is legitimate when all too often we see it play out as superficial and insincere?

By doing it well 🙂 Every time you create an example of genuine and valuable participatory governance, you will create a new baseline for people to build upon. Just do it. - How do you deal with communities who earned trust but proved to have egregious motives?

Will definitely need to unpack this one 🙂 Drop me an email or DM! - How do we get public servants to trust that we can deliver when the system/organization works against us?

By demonstrating success, working as openly as you can, and changing the system wherever you can. The system is changing, whether it wants to or not, and it is only by persistent commitment that we can steer it in the right direction. - What caused us to get to a point where the legitimacy of gov services is so low? How do we avoid this happening again?

Honestly I’ve been pondering this for a while. I think we all just adopted tech in an unthinking way in the first instance. Lawyers, policy folk, drafters and even executives considered “implementation” to not be their job, and that disengagement led to techies doing our best, with varying degrees of direction and disempowerment (usually operational policy people just throwing “business requirements” over the fence without any accountability as to the accuracy or legitimacy of those requirements). We used technology and technologists as a blunt instrument to simply mechanise the public sector, but now we have to reconnect all the different disciplines to reinstitute an approach to technology where it is an enabler for good government, not just a cost centre or means to save money. We need to move our mechanised sector to a responsive and policy/human-centred approach to how we use and deploy technology, and we need to have technologists at the table with policy, legal, drafters, now joined by design, to work together for the best public sectors that are both human centred, and trust building. - Do you have examples of how NZ has overcome the ‘constant disempowerment’ as you mentioned in your presentation today? What were the steps that made you successful?

When I worked in NZ we had a small team that was cross agency funded and cross agency governed. I can now look back and realise our success is because we lived in a small gap between the usual constraints of that system. Unfortunately the answer for NZ needs to be a systemic push to delegate more decision making further down. In Australia, significant authority is delegated down 3 levels (beyond the head of department), and sometimes even to 2 more levels beyond that. 5 levels of authority over funding decisions, program planning, team management, etc. In NZ most authority is delegated 1 level down (DCEs, etc) who then may or may not delegate further. If you want to unlock the brilliance and productivity of the NZ PS, delegation of decision making over budgets, staff, operational decision making etc needs to be pushed down at least another 2 levels to get anywhere close to where other comparable public services are at. Otherwise you need to build bubbles in the gaps, which is not sustainable. - Thank you PIA!

Aww, I’ll take that as a comment not a question, but thank you too!