Background: When I got back to Aotearoa, having worked in NSW and Canadian Governments in the interim, I thought it might be helpful to share some insights and comparison of the service delivery models of Service NSW, Service Canada and the New Zealand Government. My goal was to share what truly integrated services can look like 🙂 The paper ended up also going into proposing a “Service Aotearoa” model, and inevitably touched upon challenges around public trust and the trustworthiness of public services and public institutions. This first paper is available here for folk interested and was framed around two problem areas, namely that fractured, inconsistent and confusing service delivery is ineffective at meeting and adapting to the diverse needs of New Zealanders; and trust and truth needed to make successful policy and operate services effectively.

When the NZ Government Justice Committee Inquiry into the 2020 General Election and Referendum was calling for submissions, I thought the issues of trust and trustworthiness might be helpful to contribute, especially with the rise and weaponisation of deep fakes, which will very likely affect coming elections globally. Of course, public trust is directly impacted by the public’s experience with the public sector, which is heavily influenced by their experience with services, so the Service Aotearoa model mode it into that paper 🙂

The full paper I submitted to the Justice Committee is available here, and key excerpts are copied below for convenience. I’ve included the introduction, problem statements, and final word on why these problems are urgent to consider. Some proposed solutions and the service delivery models analysis is in the appendix of the paper 🙂

Introduction

This submission was prepared by Pia Andrews on one of the themes of the 2020 Election Inquiry, namely:

Theme 2. The integrity and security of our electoral system in light of emerging challenges, with a particular focus on technology and social media.

From the terms of reference for the Inquiry into the 2020 General Election and Referendum

The submission touches upon topics beyond this theme, and beyond the 4 themes outlined for the 2020 Election Inquiry. It addresses the impact of new technologies such as “deepfakes” and increasingly self referential social media echo chambers of misinformation, and goes further to address the key challenges of trust, truth and authenticity in the 21st century, and subsequent impact on electoral integrity.

The New Zealand General Election is a core tenet for representative democracy with free and fair elections that have the trust and respect of the community. This supports a civil society where the Government may exercise power with the explicit consent and social contract with the electorate. The public sector in New Zealand has a special role in providing a social, regulatory and financial platform upon which the community and individuals should be able to economically, socially, culturally and environmentally thrive. However, the increasing gap between the needs of New Zealanders in a digitally enabled, globalised and artificial intelligence world, and the inability of the public sector to proactively identify, respond to and holistically meet those evolving needs, creates a negative impact on public trust and confidence that can quickly extend to declining trust in public and democratic institutions.

The public sector delivery of an effective response to COVID, in partnership with the team of five million New Zealanders, initially drove public trust in some parts of the community to record levels. This trust enabled one of the world’s most effective responses, but is already declining. For trust is to be sustained and channelled into adapting to an increasingly uncertain post COVID world, there needs to be a conscious effort to address and prioritise public trust and confidence in public institutions.

If one part of the public sector is considered untrustworthy by the communities served, then we all are at risk of the serious implications of reduced public confidence and trust across the board. Reduced public confidence in the public sector leads to people simply not trusting, engaging with or respecting as legitimate the services, policies, laws or democratic outcomes administered by the public sector.

For this reason, the recommendations identified in this paper, whilst relevant to electoral integrity, go well beyond the mandate of the Electoral Commission. In the author’s view, even a strong Electoral Commission will not be able to maintain public trust or confidence in the New Zealand electoral system if trust in the broader public sector continues to decline.

My thanks to Thomas Andrews, Sean Audain, Brenda Wallace, Hamish Fraser, James Ting-Edwards and others who helped edit and peer review this submission. I hope it provides useful context, ideas and discussion points to help with future elections, but also to contribute in some small way to reforming the New Zealand Central Government public sector for the benefit of the people and communities of New Zealand Aotearoa.

The problem areas: an overview

The paper focuses on two key problem areas, both of which apply to the electoral integrity theme above and to the public sector more broadly:

- Problem 1: Authenticity and truth – people tend to believe what they see and are grappling with the way computers can convey misleading information. Deep fake technology can automate the creation of believable videos of anyone saying anything – no matter how offensive or outrageous. We are about to enter a very dark age where individuals, governments and communities are increasingly and proactively “gamed” or “played” en masse for profit, crime, sabotage or even just for fun. Beyond the authenticity of information, facts, fiction and fakes coexist online, and citizens are increasingly struggling to navigate truth. On one hand, one person’s truth is another’s lie, but there are possibly some better ways to help support citizens and communities to navigate truth in the 21st century, and to help populate the public domain with robust and trustworthy data and facts, where and when they exist.

- Problem 2: Trust in public institutions – Governments and public sectors the world over are facing an impending trust and confidence crisis, and must carefully and collaboratively engage on the question of what structures, processes, oversight and forms of transparency and public scrutiny would be considered trustworthy by the public today. Otherwise, public institutions will lose trust, as will the democratic outcomes, social and economic services, policies and laws that they uphold.

The recommendations in this submission aim to help create a sustainable pathway and meaningful progress on these two problem areas in the short to medium future, in advance of and in preparation for the next general election. The New Zealand public service is far from alone in emerging from the COVID-19 crisis into a world that has experienced profound changes. Internationally, these changes have led to a clear divergence in strategy between:

- governments who desire a “return to a pre COVID normal”; versus

- governments for whom “return to normal” is considered infeasible, undesirable or unwise, and seek instead to transform themselves in response to new economic, social and climate realities.

Governments in the latter category are prioritising major policy, structural and service delivery reform to ensure greater policy agility and improved quality of life outcomes. This crisis is a key motivator for writing this discussion paper to encourage the New Zealand Government and public sector to discuss immediate and systemic reforms and consciously decide whether New Zealand intends to “return to normal” or genuinely “build back better”.

Key recommendations in this submission fall under two high level proposals, both of which would include a range of initiatives:

- Proposal 1: That the New Zealand Government establishes a Taskforce to understand what New Zealanders need to better navigate truth and authenticity and explore the potential role(s) of the public sector, fourth estate and other sectors in supporting this, now and into the future.

- Proposal 2: That the New Zealand Government establishes a program [which includes building trustworthy governance, decision making and infrastructure, as well as building trustworthy public services] to improve and safeguard the trust of New Zealanders in public institutions, including the critical establishment of participatory and trustworthy governance that improves quality of life for New Zealanders.

Please see the problem areas and respective proposals outlined below.

Problem 1: the general public has decreasing means of effectively navigating truth and authenticity online

A key problem facing democracy and electoral integrity internationally is the growing reach and sophistication of misinformation and deepfake technologies in a context of declining trust in information institutions (such as news media, science, academia and public sectors). These concepts are not simply headline-grabbing or political soundbites imported from other jurisdictions. They are serious and growing challenges to truth, and are increasingly being used for gaming public opinion by foreign and domestic actors (human and machine), with very few mechanisms to effectively counter or mitigate the effects thereof. We can consider misinformation and the dissemination thereof, as two problems:

“At a US Senate intelligence committee hearing in May last year, the Republican senator Marco Rubio warned that deepfakes would be used in “the next wave of attacks against America and western democracies”. Rubio imagined a scenario in which a provocative clip could go viral on the eve of an election, before analysts were able to determine it was a fake.

“Democracies appear to be gravely threatened by the speed at which disinformation can be created and spread via social media, where the incentive to share the most sensationalist content outweighs the incentive to perform the tiresome work of verification” (Parkin, 2019).

Parkin, S. The Rise of Deepfake the the Threat to Democracy, (2019), The Guardian

The New Zealand Law Society commissioned a report into deepfakes in 2019 (Distorting Reality: Deepfakes and the Rise of Deception), which has a range of recommendations worth considering but it also makes the point that the main threat is from international and machine/AI sources, so domestic laws will not provide much protection.

The issues of truth and trust are integral to the relationship between government and citizens, and as seen from developments in other democracies, and the threats from digital deep fakes, social media misinformation campaigns and similar technologies has become a realised and growing danger. In the past we have relied upon independent media institutions and broadcasting controls to identify and mitigate these risks but with the disruption and bypassing of these channels through self-reinforcing social media echo chambers online, combined with exponential growth in misinformation, it is clear that the implications for future elections, public messaging, public policy and social cohesion are potentially dire. The question for government is what role, if any, should the public sector or the judiciary play in trying to support citizens to navigate these treacherous waters?

It is critical to start this work as soon as possible, so that New Zealand is in a position to have a well supported general public (or at least means to support the general public) prior to the next election, which will likely be rife with deep fakes that will create chaos for public dialogue, civility and perceived electoral integrity. Such misinformation also creates profound security threats, and whilst our intelligence agencies have traditionally provided a degree of protection against such threats, the highly permeable, borderless and individual worlds created by social media suggest that partnership with more community based methods will be required to ensure the sector can continue to meet the challenge of higher order threats to New Zealand’s security.

Problem 2: Proactively building public trust in public institutions is important to social, economic and democratic stability in New Zealand

Public sectors globally are struggling to shift from simply seeking permission (or social licence), to actually operating in a more trustworthy way. This means reimagining public institutions and governance in the digital age to take into account the impact, opportunities and challenges of the internet, of increasingly empowered individuals and communities, of economic and cultural globalisation, and of greater public expectations for effective and human centred public services. In an era also characterised by increasing change and rolling emergencies (pandemics, environmental, terrorism, regional instability, cyber threats, etc), it is critical and urgent to improve and stabilise trust in public institutions, and establish participatory, trustworthy and beneficial (to society) governance that people can rely upon with confidence. This includes necessarily reimagining and transforming the public sector to be holistic, proactive, collaborative and citizen-centric. To enable this stability and advancement, the public must be able to trust in a public sector that conducts itself on a reliable, referenceable and transparent foundation of truth and trustworthy accountability.

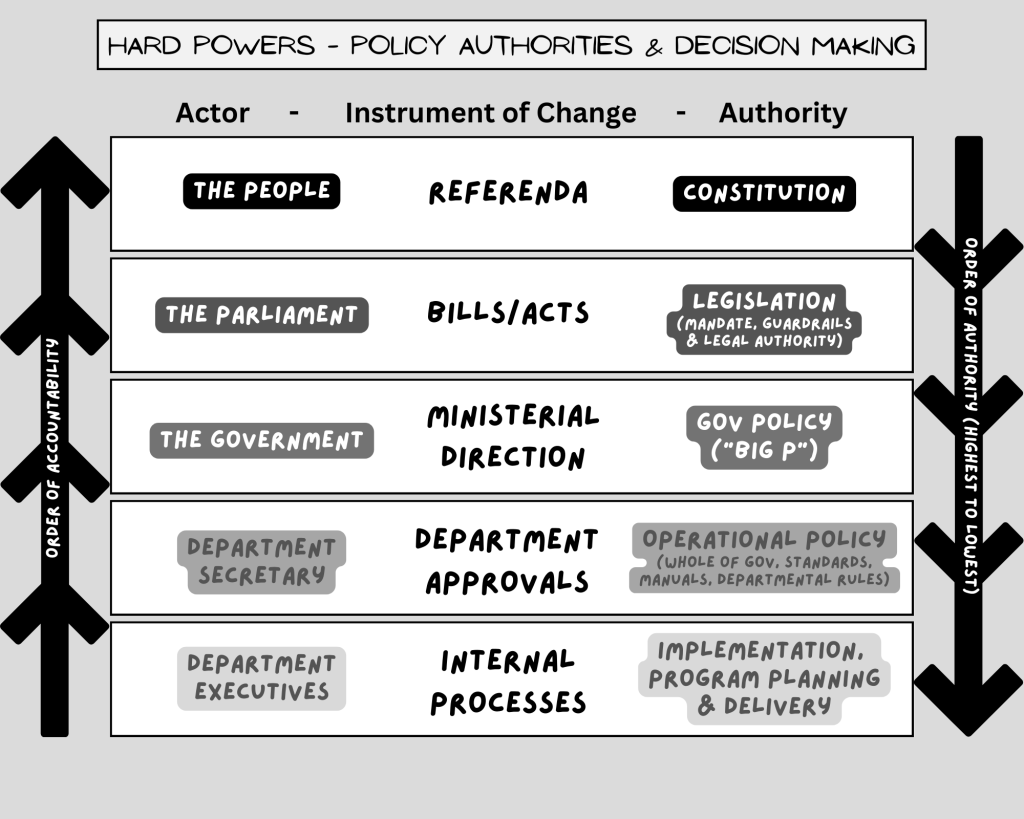

Operating in a trustworthy way means first acknowledging that the public needs to be confident in public servants’ decisions and actions to be able to trust the outcomes of our efforts. To operate in a trustworthy way, the public should be engaged up front in co-designing what “good” would look like, which would necessarily involve public visibility to the accountability, transparency and oversight mechanisms of governance. This includes ease of appealability and auditability of government policies, services, regulations and programs, and parity across the system. One department operating in a way that erodes public trust has a net trust deficit impact on all public institutions, so certain norms must prevail across the sector. For instance, taxation rules are quite easy to find and apply, and yet entitlement and eligibility of social services are hard to determine and are kept more obscure. Another example is how some statistics are readily available to the public, but the respective success metrics and reporting of individual programs and policies is far harder to find.

Public institutions exist to support public good and quality of life, so there should never be a stronger imperative than ensuring and promoting that New Zealanders get the support and services they are eligible for and entitled to. Yet, we often see short term pressures (like reduced or reprioritised budgets, failing IT systems or the latest Ministerial priority) drive a lot of reactive behaviours and short term planning in the public sector. It is critical that the public sector always take the long view and plan resources accordingly. It is important that the public sector equally serve the Government of the day, the Parliament and the People, in a balanced, independent and sustainable way that maintains the trust of them all.

The concept of public infrastructure as it relates to public health, public education and public transport is fairly well understood, but where is the public digital infrastructure that our communities and various sectors should be able to rely upon and trust? For instance, where is the publicly available reference implementation of machine readable legislation and regulation for ease of service delivery, compliance and public scrutiny? Or the list of all public services with the respective eligibility and calculation information? Or the proactive and public modelling tools to understand the impact of change or emergencies? Where is the publicly accessible record of key decisions and actions taken, with traceability to their legal or policy authority? There is so much confidence the public sector could inspire by simply working more in the light, and less in darkness. To be fair, much of the opaqueness of governance is simply a matter of habit and inherited practices, but the lack of genuine systemic transformation has led us to a point where the New Zealand public sector is, as a whole, several steps behind the society and economy it purports to serve.

Public sector services must also be considered trustworthy, as citizens want to feel supported, empowered, respected and confident in the public sector to help them when they need it. Reform of public sector services is a critical part of ensuring and growing public trust in public institutions. Modern government is complex in any dimension, be it scale, number of services or processes followed. As the public sector seeks to embrace tools like AI to deliver outcomes and greater value to taxpayers, it is important to understand how these technologies interact with NZ laws and institutions. In this respect, New Zealand would be better served by an informed democracy than it would be by just a data driven governance. In aiming for an informed and participatory democracy, the explainability and transparency of a decision is a key building block.

Explainability and transparency of AI and data analytics components is vital to understanding issues of bias, exception and application within these decision making processes and are critical to upholding the principles of Administrative Law in an increasingly technologically powered public sector. In short the advice and actions of the public service derived from digital tools must be able to be seen and explained. Capturing and assuring the explainability of a decision or action taken by the public service is critical for the ability to audit, appeal, and maintain both the reality and perception of integrity of our public institutions. It is also critical for ensuring the actions and decisions are lawful, permitted, correctly executed and properly recorded for posterity. It is also important to ensure and regularly test the end-to-end explainability and capture of decisions and information for the work done in the public sector, especially where it relates to anything that directly impacts people — like social services, taxation, justice, regulation, or penalties. Moves like the Algorithm Charter from StatsNZ are only a first step to addressing these issues.

To be a trusted advisor for an informed democracy, the public sector has ALWAYS required to explain administrative decision-making. It also means a high requirement on public servants to differentiate fact from fiction. Administrative Law principles require that decision-makers only make decisions within their delegated power, take into account relevant evidence, and provide their decision together with reasons and authority for the decision and avenue for appeal. The public sector is uniquely experienced and obligated in this respect. The public service challenge is to mobilise this experience and ensure the principle and practice of Administrative Law is upheld in an increasingly complex technologically and data-driven public sector.

As we plan for the potential impacts enter the age of Artificial Intelligence, public sectors should also be actively planning what an augmented society and public sector looks like, one that embeds values, trust and accountability at the heart of what we do, whilst using machines to support better responsiveness, modelling, service delivery and to maintain diligent and proactive protection of the people, whānau and communities we serve. There is a serious opportunity to combine modern tools with participatory governance to reimagine and humanise government policies and services. As it stands, the incremental and iterative implementations of new technologies, including most AI projects, are likely to deliver more inhuman and mechanised public services. New Zealand risks missing the opportunity to design a modern public service that gets the best of humans and machines working together for the best public and community outcomes. The worst possible outcome is to be continually playing catch-up against the rapidly evolving misinformation technologies that already exist and which have already been deployed against the general population.

There has been recent precedent on the legitimacy of automated decision making and auditability in the Australian courts. In late 2018 the landmark court case of (Joe Pintarich v Deputy Commissioner of Taxation) ruled that an automated piece of correspondence was not considered a ‘decision’ because there was no mental process accompanying it. This creates a question of legitimacy for all machine-generated decisions in Australia as was stated in substantial detail by the dissenting judge. But it should also be a major driver for agencies to invest in and mandate explainability for all significant decision-making, recorded for posterity, so that decisions can be trusted.

The important work to transform the public sector to operate in a more trustworthy way would result in open, engaged, auditable and fair government for the digital age, with high quality and trusted services that provide a dignified experience for New Zealanders and a genuine increase in public trust and confidence in public institutions. This would position government sectors, services, policies and capabilities as trusted and adaptive foundations of New Zealand’s future.

The Proposals

The proposals in full are in the full paper I submitted to the Justice Committee is, available here. Below is the high level overview of proposals to the problem statements above:

Proposal 1: establish a Taskforce or programme to understand needs and develop strategies for supporting New Zealanders to navigate truth and authenticity online, ahead of the next election

Below are some specific recommendations a Taskforce could consider for the next election and beyond::

- It would clearly be impossible to provide a service to verify the authenticity of all information on the internet for citizens. The scale of new content being generated, by humans and increasingly by bots and software, is impossible to manage through traditional escalation and review methods. But there are some types of information that could be made available in a more verifiable way, for example official or political content. The Electoral Commission could provide a realtime electoral, political and public sector messages/information validation service. Citizens could use such a service to check the authenticity/source of political and official messages about the next election and to distinguish deep fakes from authentic official materials. This can be complemented with public awareness campaigns.

- Provide education services, directly and in partnership with trusted community entities and organisations, with a campaign to raise public awareness about misinformation, deep fakes and the increasing likelihood of being actively gamed by domestic and international actors, especially around election time. f

- The Electoral Commission could engage with, and support, trusted and community initiatives that identify and mitigate misinformation, such as the recent efforts by Tohatoha and other organisations in New Zealand. Ideally this would be done in collaboration with the Fourth Estate to help rapidly debunk emergent misinformation campaigns quickly for and to the general public.

- The New Zealand Government could consider all information for which the public sector is authoritative, to be mandated as being publicly available for reuse, for validation and to help contribute facts and data to the public domain.

- It is worth noting the New Zealand Police and intelligence agencies already monitor for and engage with the community around misinformation, as it is directly linked to security threats and radicalisation efforts. Some of the intelligence from these operations could potentially feed into broader public engagement efforts early, as they are likely in a position to identify early patterns of misinformation. The Taskforce could work with the NZ Police and intelligence agencies to consider the flow of information and early patterns and indicators of misinformation and better leverage these systems and operations for broader public engagement and support services.

- The people of New Zealand have a broad range of independent organisations they trust and engage with every day. If the New Zealand Government collaborated with and shared information, patterns, and insights to entities and organisations that the public trust, including Iwis, public libraries, and Citizen Advice Bureaus, it would help them support their communities navigate truth and authenticity. Such information services would need to be constrained to factual information because if such a pipeline of information was set up and used in any way for political or ideologically motivated information sharing, then those organisations would disengage entirely.

Proposal 2: A programme of public sector reforms to improve and safeguard the trust of New Zealanders in public institutions

In order to grow and sustain public trust, the public sector needs to be more accessible, transparent, responsive to and engaged with the people and whānau served. Generating trust is difficult and complex due to collective experiences, and the personal nature of relationships that trust is built from. Trust in the public sector could be dramatically improved in two key ways, both of which apply to the Electoral Commission, but must also apply across all portfolios:

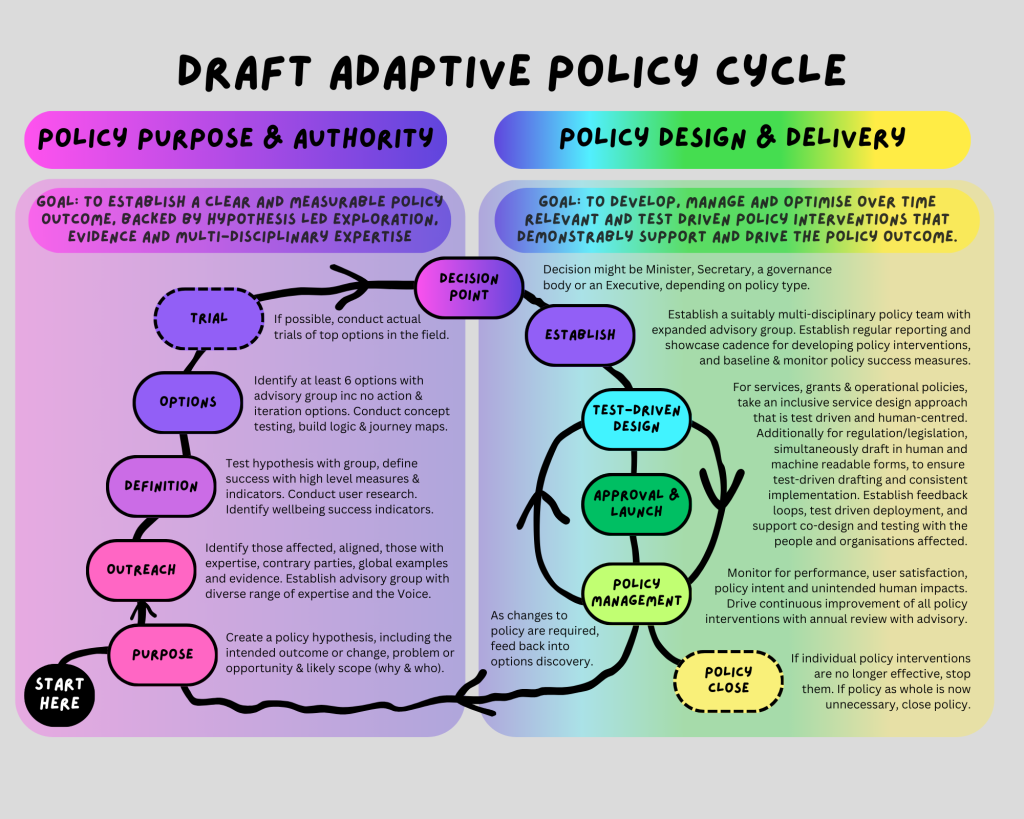

2.1 – Establish and implement dramatically more trustworthy and participatory practices and governance of public institutions, public policies and public services, that takes into account and plans for modern and emerging technologies, increasing change of community needs and the environment in which we live, and the need to partner with people and communities in shaping policies and services.

2.2 Dramatically improve the quality, availability and delivery of public services to the people and communities of New Zealand, to better serve people and ensure they get the help they need and are entitled to.

Last word: What changed? Why is this urgent now?

Public sectors around the world are facing increasing challenges as the speed, scale and complexity of modern life grows exponentially. The 21st century is known as the anthropocene – as large, complex and globalised systems enmesh our societies on a scale unseen in previous history. The 20th century saw a global population rise from 1.6 billion to 6 billion, two world wars that spurred the creation of global power and economic structures as well as enduring global divisions, and the number of nations rose from 77 to almost 200. The twentieth century also saw the emergence of a global middle class, an enormous increase in living standards and the emergence of the internet and digital technologies. These global megatrends have changed the experience, connectivity, access to knowledge, and empowerment of individual people everywhere. As humanity has bound itself together in integrated global systems this has also integrated the shocks and stresses experienced by those systems into global experiences such as climate change, COVID19 and fundamental restructurings of the global economy. The public sector must continue to serve in this evolving, integrated context leading to new challenges for democracies worldwide.

The public sector has an important role in a society like New Zealand Aotearoa not only to a) serve democracy, but also to b) support a high quality of life for New Zealand, and c) maintain economic and social balance through various types of direct and indirect regulation, services, and public infrastructure. It is therefore critical that we take a moment to consider the role(s) of the public sector in the 21st century, and whether there are any new areas of need that the public service could play a unique role in supporting or regulating.

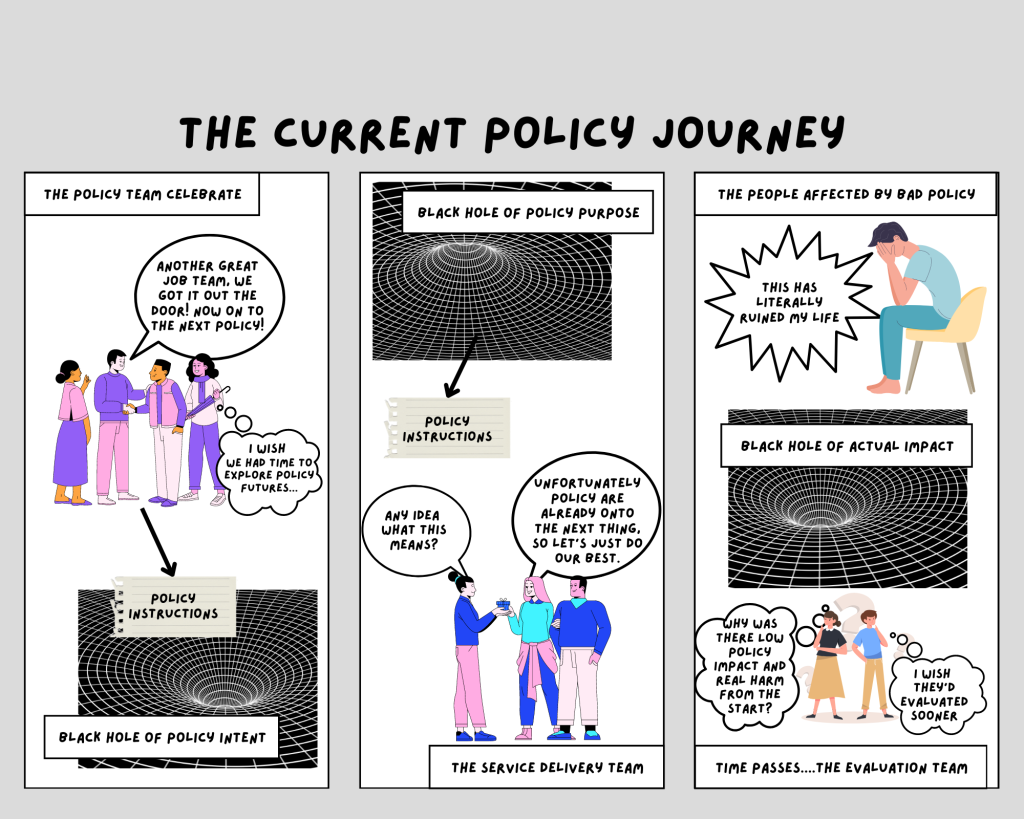

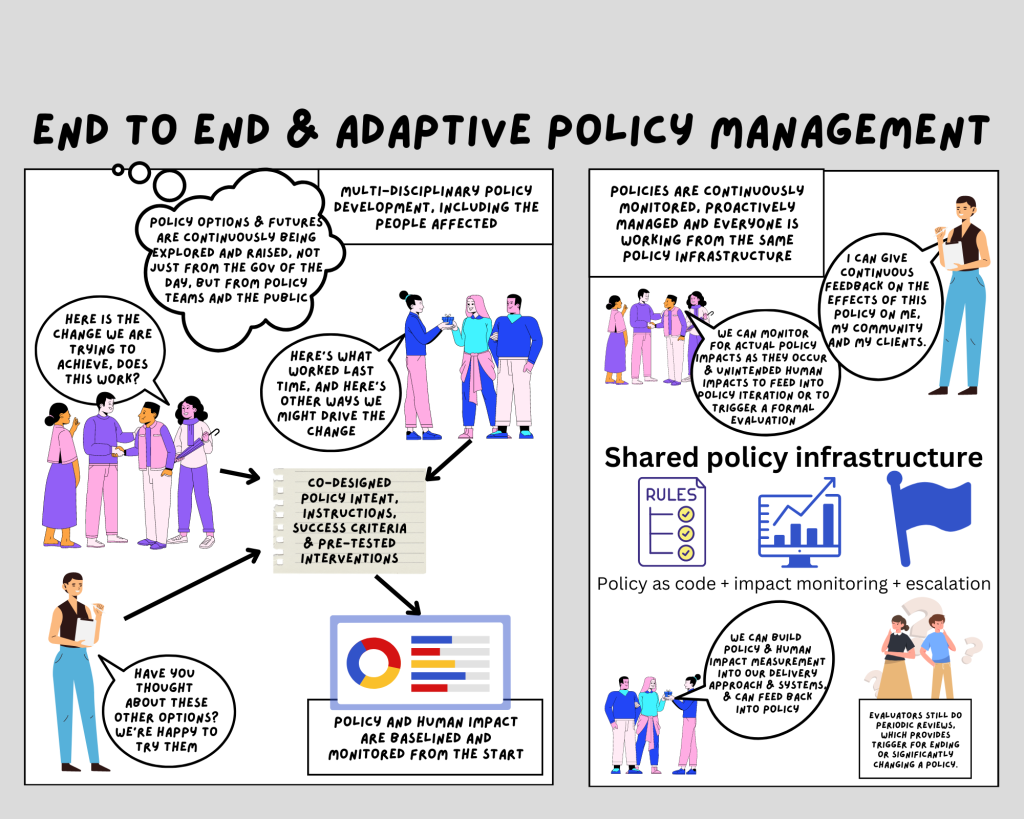

“Traditional” approaches to policy, service delivery and regulation were designed in an analog and industrial age and are increasingly slow and ineffective, with increasingly hard to predict outcomes and unintended consequences given the dramatic increase of complexity and interdependency today. The functional separation between policy and implementation over recent decades further compounded these issues, and created unnecessarily siloed operations with limitations on end to end visibility of policy delivery. Most public sectors are now simply unable to meet the changing needs of the people and communities we serve at the speed of change with any level of certainty or agility. Decades of austerity, hollowing out expertise, fragmentation of interdependent functions that are forced to compete, outsourcing and the inevitable growing existential crisis have all left public sectors less prepared than ever, at a time when people most need us. Public sectors have become too reactive, constantly pivoting all efforts to the latest emergency, media release or Ministerial whim, whilst not investing in baseline systems/capabilities, transformation, programs or new services that are needed to be proactive and resilient.

Policy and delivery folk should be hand in hand throughout the entire process and the baton passing between functionally segmented teams must end.

COVID has been a dramatic reminder of the broad ineffectiveness of government systems to respond to rapidly changing needs, in three (3) distinct ways. We saw:

- the heavy use of emergency powers relied upon to get anything of substance done, demonstrating key systemic barriers, but rather than changing the problematic business as usual processes, many are reverting to usual practice as soon as practical.

- superhuman efforts that barely scratched the surface of the problems. The usual resourcing response to pressure it to just increase resources rather than to change how we respond to the problem, but there are not exponential resources available, so ironically,

- inequities have been compounded by governments pressing on the same old levers with the same old processes without being able to measure, monitor and iterative or pivot in real time in response to the impacts of change.

With COVID driving an unprecedented amount of change in public sectors globally, it makes sense to consider machinery of government assumptions and what “good” looks like in the 21st century.

In late 2020, there was a major UNDP summit called NextGenGov, where all attendees reflected the same sentiment that public sectors need significant reform to be effective and responsive to rolling emergencies moving forward. Dr Sania Nishtar (Special Assistant to the Prime Minister of Pakistan on Poverty Alleviation and Social Protection) put it best:

‘it is neither feasible nor desirable to return to pre-COVID status quo’.

Something to reflect on, for all of us. It is a final and timely reminder that if we are to transform our public sectors to be trustworthy and fit for purpose in the 21st century, then we need to take just a little time to collaboratively design what “good” would look like for New Zealand Aotearoa, and by extension what is required from the public sector to support that vision. Otherwise we run the risk of continuously just playing whack-a-mole with emerging problems and reinventing the past with shiny new things.