TL;DR: Better policy design and evaluation won’t save us 🙂

The APS Reform agenda provides a rare window of opportunity to address structural and systemic issues in the APS, so why not explore how might we transform the way policy is designed, delivered and managed end to end?

Why should we reform how we do policy? Simple. Because the gap between policy design and delivery has become the biggest barrier to delivering good public services and policy outcomes, and is a challenge most public servants experience daily, directly or indirectly. This gap wasn’t always the case, with policy design and delivery separated as part of the New Public Management reforms in the 90s. When you also consider the accelerating rate of change, increasing cadence of emergencies, and the massive speed and scale of new technologies, you could argue that end-to-end policy reform is our most urgent problem to solve.

Policy teams globally have been exploring new design methods like human-centred design, test-driven iteration (agile), and multi-disciplinary teams that get policy end users in the room (eg, NSW Policy Lab). There has also been an increased focus on improving policy evaluation across the world (eg, the Australian Centre for Evaluation). In both cases, I’m delighted to see innovative approaches being normalised across the policy profession, but it has become obvious that improving design and/or evaluation is still far from sufficient to drive better (or more humane) policy outcomes in an ever changing world. It is not only the current systemic inability to detect and respond to unintended consequences that emerge, but the lack of policy agility that perpetuates issues even long after they might be identified.

Below I outline four current challenges for policy management and a couple of potential solutions, as something of a discussion starter 🙂

Current policy problems

Problem 1) The separation of (and mutual incomprehension between) policy design, delivery and the public

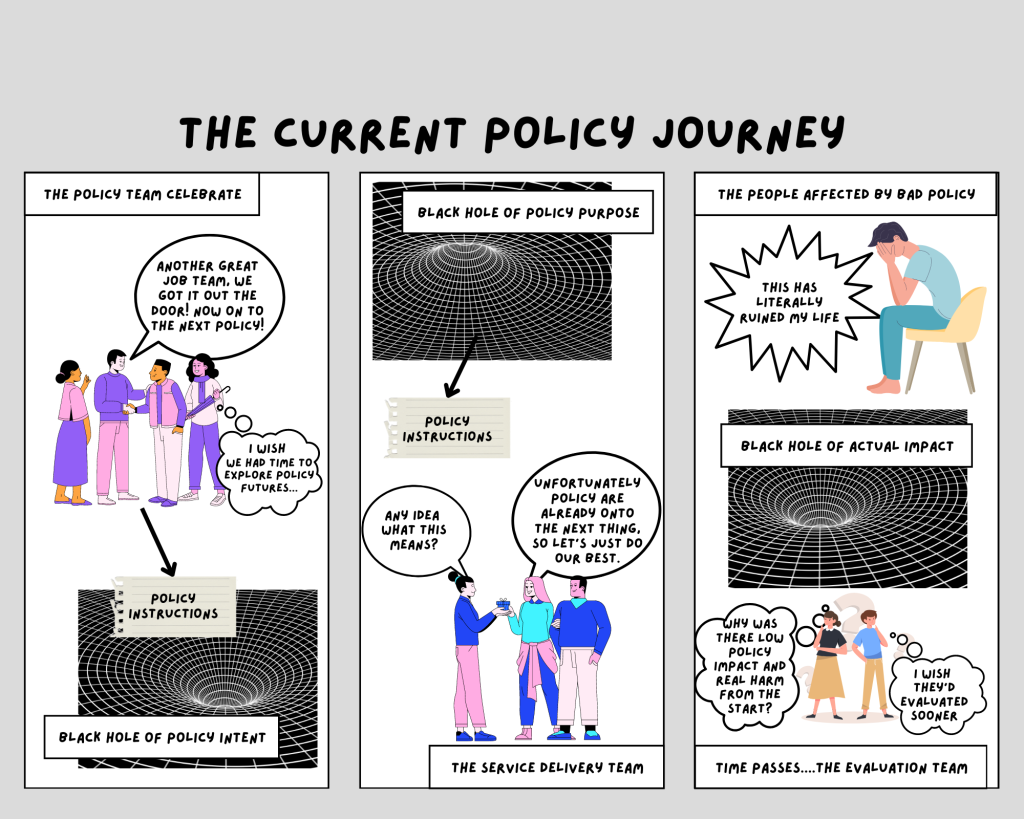

The lack of multi-disciplinary policy design, combined with a set-and-forget approach to policy, combined with delivery teams being left to interpret policy instructions without support, combined with a gap and interpretation inconsistency between policy modeling systems and policy delivery systems, all combined with a lack of feedback loops into improving policy over time, has led to a series of black holes throughout the process. Tweaking the process as it currently stands will not fix the black holes. We need a more holistic model for policy design, delivery and management.

CC-BY: Pia Andrews, 2023

There is also a significant gap with the public. From the start, there is usually a lack of diversity in expertise and experience in shaping a policy, and once an intervention is decided and rolled out, the people affected by policies have limited means to give feedback. Engaging the public early and often, and then providing clear feedback loops would help policies be better designed and improved over time.

Problem 2) The lack of real time monitoring of intended AND unintended impacts

The laudable efforts to improve policy evaluation are great, but formal evaluations usually have two limitations that could be better addressed with other mechanisms. Firstly, formal evaluations often tend to be positivist, in that they look for “has this initiative delivered what it said it would”, and aren’t often driven or set up to explore and understand unintended impacts, such as human or environmental patterns that emerged as a result of a new policy interacting in a complex domain.

Secondly, formal evaluations are usually a point in time assessment, rather than real time monitoring of policy impacts. Evaluation teams are not connected to the day to day delivery of policy interventions, creating a timeliness challenge in mitigating issues that are identified. Evolving and improving policy evaluation methods will create greater understanding, but perhaps too little, too late for those affected in between. Real time monitoring of intended and unintended impacts would nicely complement formal evaluation methods, while also providing a timely trigger if anything trended in the wrong direction.

Problem 3) A systemic inability to iterate policy in response to impact, feedback or change

Policies are often designed by a policy team, and then handed over to implementation, so that policy team can move on to the next policy priority, creating a systemic inability to iterate policies as the real impacts are felt in delivery. It doesn’t matter how collaborative or inclusive you are in designing a policy, there will always be perpetual change in the environment, and unintended impacts to mitigate. We need to take the lessons from the creation of “Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery” (CI/CD) pipelines in service delivery, to create a “CI/CD Policy” approach which would manage policy design and delivery as part of the one continuum, drawing upon continuous feedback loops, monitoring and measurement of policy and human impacts to inform and iterate policies and the respective interventions. This would not only help policies to maximise the realisation of policy intent in a rapidly changing world, but would also provide the means to proactively identify and manage policy impacts (positive and negative) as they emerge.

Problem 4) Inconsistency in policy literacy and practice across the sector

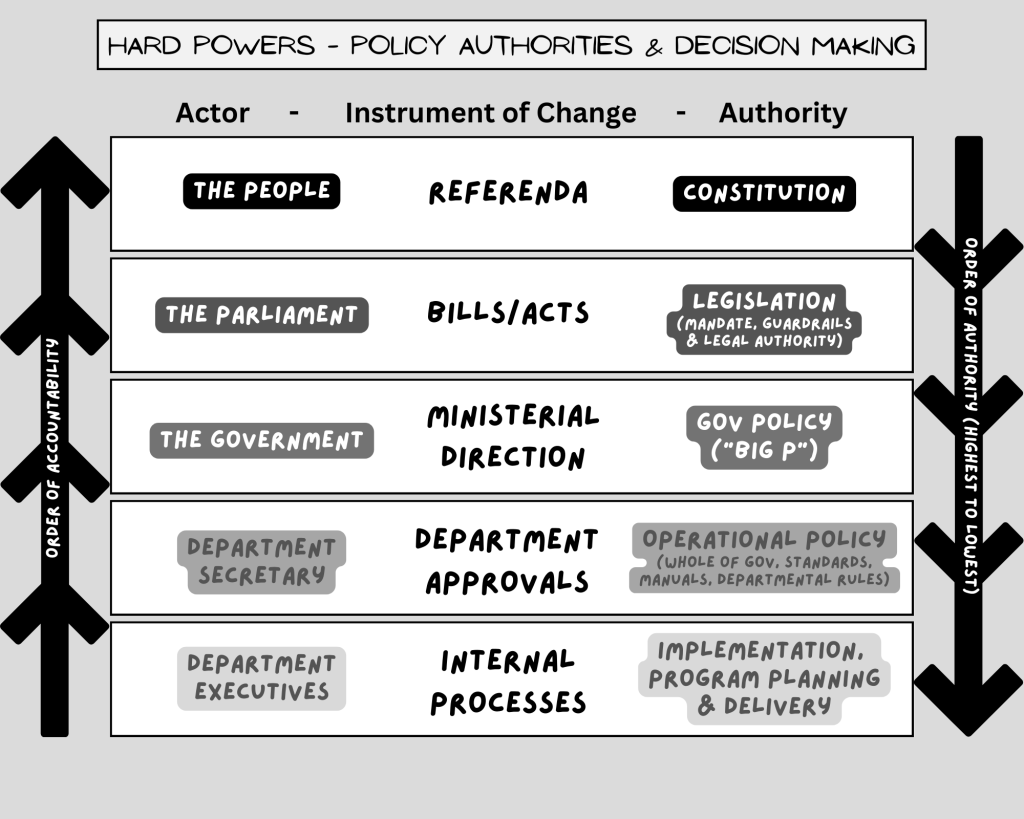

Last, but not least, is the inconsistent definition, context and practice of “policy” across the sector, creating confusion and real issues of authority, decision making and accountability. Unfortunately today, many of the “policy guides” currently available limit themselves to Government Policy development, which has led to the common but dangerous assumption that Government Policies are the highest authority, and that the peak of good public service is to simply advise the Government.

To my mind, there are three highest level and fundamental categories of “policy”:

- Foundational Policies: the constitution, legislation and regulations which provide the context, framing and highest legal authorities and accountabilities of a department;

- Government Policies: the directions of the Government of the day via the respective Ministers, which is subject to foundational policy limitations; and

- Operational Policies: which covers all the operational, whole-of-government, department-defined rules and delegated policies, which are subject to both the government and foundational policy directions, but are the authorititative domain of Secretaries.

The diagram below provides a useful reference on the hierarchy of authority of different policy types, as well as a guide to decision making involved in each. This should help public servants realise that different actors are needed for change to different policy types, and that even Ministerial directions are constrained by the Foundational Policies above. It also should provide public servants more understanding as to what decision making is actually within their delegated authority, such as operational policies.

CC-BY: Pia Andrews, 2023

Potential solutions

Solution #1: Adaptive policy management

So what might adaptive policy management look like? Well, let’s start with what the characteristics for delivering great policy and human outcomes might look like, and then we can reverse engineer an ideal policy operating model we could work towards.

| From | To |

| Narrowly informed, largely driven by generalist policy professionals, with occasional expertise or end user input. | Multidisciplinary and diverse expertise and experience informing the whole process, including early testing of several interventions with representatives of those affected. |

| Static policies are defined, the policy team moves on, policy change is slow and difficult, often principles-based and subject to varied interpretation in delivery. | Dynamic policies, with policy expertise present in policy interventions end to end (leg, services, reg, programs, grants, etc) with continuous, evidence-based policy iteration. |

| Reactive to issues, as they are identified. Constantly looking backwards, mitigating symptoms, without time to look forwards or address causes. | Responsive to change as it happens, monitoring for impact (intended and unintended) and constantly adaptive to change in a forward looking way. |

| Assumptions driven, policy interventions are based on past or current assumptions, without testing, exploring or co-designing a range of approaches. | Test driven, a diverse range of potential policy interventions are explored, with a range of stakeholders, with feasible options tested prior to finalising policy options or ratifications. |

| Culturally exclusive, policies are developed without culturally diverse experience or expertise. | Culturally inclusive, policies are developed in a culturally inclusive way, embracing diverse knowledge systems and methods. |

| Split policy infrastructure, where policy design and modeling happen in one place, but policy delivery happens in a different place, leading to inconsistencies in implementation assumptions, and the inability for policy owners to monitor the reality of policy implementation. Modeling is often limited in scope and domain, so policy conflicts are only identified in delivery, too late to inform design. | Shared policy infrastructure, common and shared digital policy models are used for both modeling/design and delivery, such that there is no gap between the two. Policy owners can have higher confidence in the likely impacts of change, whilst also keeping a finger on the pulse of actual policy impacts. Policy intent and impact are monitored alongside performance and CX measures, and feedback loops loop back to policy. |

| Policy realisation is slow, as the whole lifecycle requires policy options, legislation/regulation, operational policy development, with several opportunities for misinterpretation. Policy intent can take years to even start to be realised. | Policy realisation is fast, policies are developed in a faster way with reference implementations resulting from rapid and test driven drafting of human and machine readable policy. This results in better rules & dramatically speeds up implementation. |

| Community engagement, engaging the public in research or testing ideas is currently ad hoc and inconsistent. | Community empowerment, could refer to both the ability for communities to generate new policy ideas with government, but also that public sectors attempt to devolve more decision making on policy or investment to communities. |

Perhaps policy making could be more of a team sport:

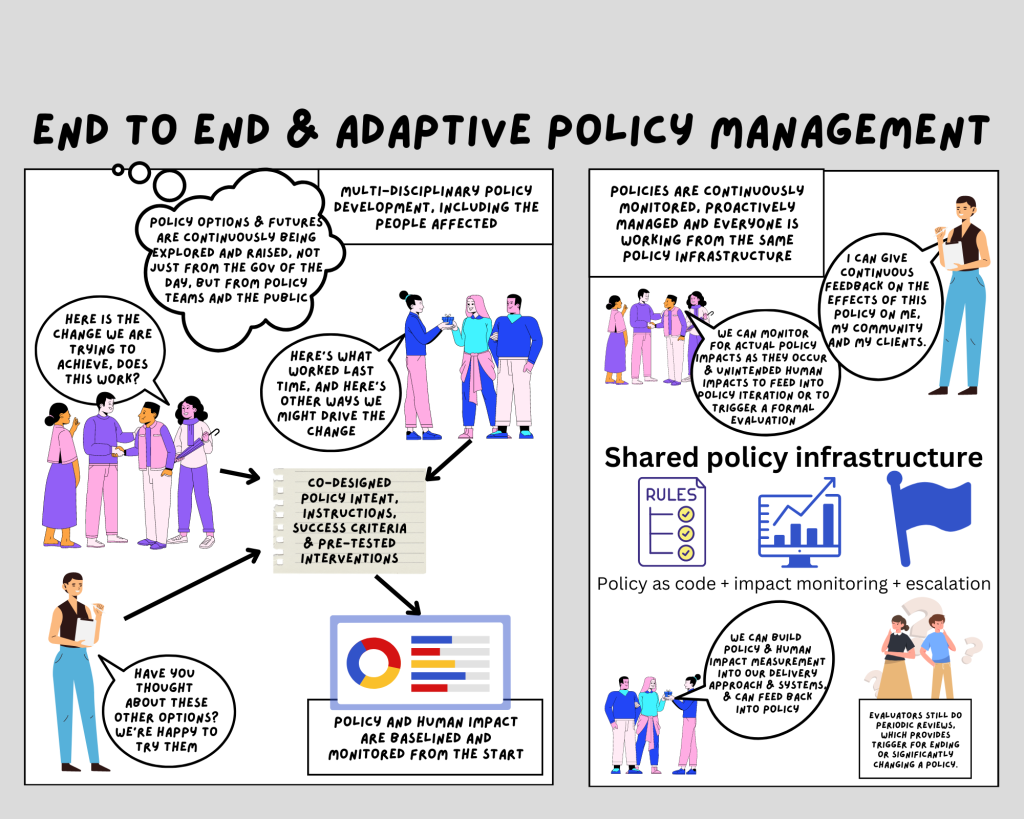

CC-BY: Pia Andrews, 2023

Below is a high level potential approach to the policy lifecycle, where policies are designed and delivered collaboratively, with shared policy infrastructure, and real impacts monitored, escalated and fed into policy improvements over time, with formal evaluations able to be triggered when things go terribly wrong, not years later. Policy makers could, for instance, establish a theory of change between the vision / outcomes and the actions being taken, to ensure the indicators and measures are connected to and represented in delivery from the start. If all policies required a purpose statement, it would help implementers to ensure the delivery was aligned to the purpose and intent of the policies.

CC-BY: Pia Andrews, 2023

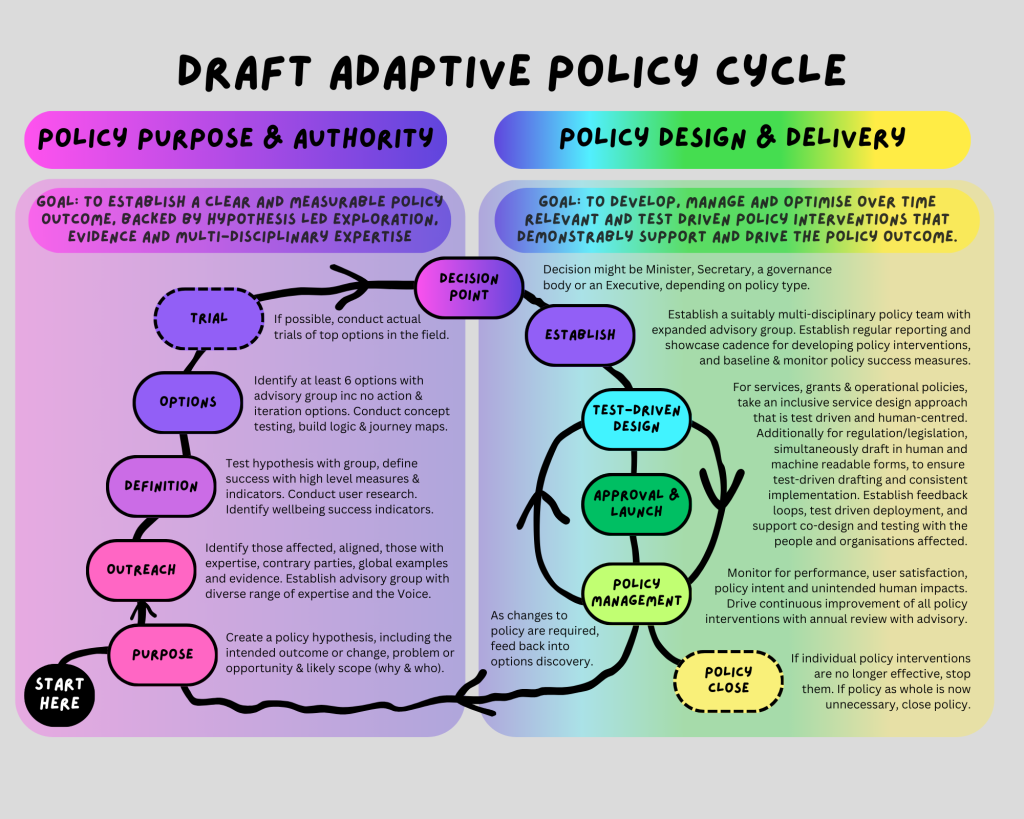

In this model, there is only two phases in the policy lifecycle:

- Policy purpose and authority – collaboratively developing the overarching policy purpose/intent, definition of success, and exploring options with a wide range of stakeholders, experts and those affected by the policy, including options testing, with clear definition of the measurable change(s) that should result, and the problem or opportunity the policy is trying to address. This all leads to a decision point, which varies according to the policy type above.

- Policy interventions design & delivery – this includes the end to end co-design and management of all related policy interventions, including the program(s), services, grants, rules/legislation/regulation, or operational policy development. Policy interventions are continuously monitored individually and at a portfolio level for intended and unintended impacts, constantly improved and iterated based on feedback loops, and improvements are fed where relevant back into iterating overarching policies based on evidence and expertise.

Any form of policy could follow this model. Whether Constitutional reform, legislation/regulation reform, advice/options to Government, whole of government policies or operational policies, the intended outcome can be better realised through being a little more test-driven, participatory, multidisciplinary, iterative and through managing the whole policy lifecycle as an end to end approach with real time and continuous improvements to interventions (like services, regulations, etc), while also continuously monitoring for policy impact that can feed into policy improvements.

Proposals for reforming how policy is done are often – understandably – met with concerns at “slowing things down”. But if you look at the full journey of policy today, policy intent realisation is already quite slow. If we had a more end to end and test driven approach, we’d get better policies designed that are easier and faster to implement, which would dramatically shorten the time to realise policy intent, even if it means a little more time up front.

Solution #2: A focus and expansion of policy professionalism in the APS

We need to not only teach what all types of “good” public policy looks like, but create a culture of continuous learning and improvement for policy professionals. Perhaps we could start by complementing the excellent digital, data, HR and strategy professions coordinated by the APSC, with a “Policy Profession”? 🙂

But we also need to teach public service craft to all public servants, including what a healthy, politically neutral and evidence-based approach to public administration looks like, and why we aren’t achieving it as a norm across the sector. For instance, we need to have clear and consistent guidance on how to engage with Ministerial offices appropriately, so that everyone can maintain the integrity, dignity and trustworthiness expected of our public institutions. We also need clear guidance on how to promote an open APS that engages appropriately and regularly with the community, something which will hopefully be addressed in the APS Reform Agenda proposed Charter of Partnerships and Engagement.

All public servants should be confident to maintain real and long term stewardship of public good, above and beyond day to day pressures or policy objectives, and also be knowledgeable of their foundational policy accountabilities, which are found in the constitution and relevant legislation and regulations. For instance, I have been surprised and somewhat horrified to hear people talk about how AI is a problem in government because it isn’t regulated, seemingly unaware that all government systems, regardless of the technology, are subject to Administrative Law, the Privacy Act, PGPA and many other foundational policies (leg/reg). We have many checks and balances we can use to ensure good governance, we just need to be aware of and apply them more consistently across the whole sector. For example, here is a paper where I documented the “special context of government” and then applied that special context to the use of AI in government. It resulted in a holistic approach that is complementary to the concept and practice of responsible government. When everyone has a shared and common understanding of the special context and responsibilities of the public service, we have a good chance to get shared and high integrity approaches to everything we design, deliver and administer in the public sector.

Solution #3: Shared and end to end “Policy Infrastructure”

Given how long this post has become, I’ll share more on this concept in a subsequent post, but here’s a teaser 😉 Basically, whilst difference teams have different tools, including distinct and separate interpretations of policy, then we’ll continue to see an interpretation gap, and a lack of end to end policy visibility, which impedes end to end policy management.

CC-BY: Pia Andrews, 2023

· To support test-driven policy ideation and announcements (pink):

o Public engagement tools to explore, co-design & test policy options, both initially (new policies) & ongoing (continuous improvement to policies and policy interventions).

o Linked and integrated admin data for research, policy modelling & patterns monitoring, best hosted by an independent, highly trusted entity, like the ABS.

o Case law and gazettes as a utility to use for analysis and to test new ideas.

o Publicly available modeling tools for testing and exploring policy change.

· To support test-driven policy design, development & drafting (purple):

o Consistently applied Human Impact Measurement Framework used across government, including for new policy proposals and for monitoring.

o Public repository to share policy tools, government models, measurement frameworks, synthetic population data, etc.

· To support the Parliamentary publishing and visibility (aqua):

o A linked data representation of the administrative orders to automate reporting, accountability, auditing, security, access & to streamline MOGs.

o Publicly available Policy as code (intended outcomes, legislation, models, defined target group) available at api.legislation.gov.au

o Policy catalogue where all operational and Government policies can be discovered, along with measures and transparent reporting of progress.

· To support policy implementation (green):

o A “Citizen’s ledger” to record all decisions with traceable explanations, for auditing & citizen access

o Policy test suite to validate legality of system outputs in gov services & regulated entities.

· To support policy compliance, iteration & improvement over time (yellow):

o Open Feedback loops for public and staff about policies & services, to drive continuous improvement and to identify and mitigate harm.

o Continuous monitoring of policy & human impacts, including dark patterns & quality of life indicators, alongside usual systems monitoring, to ensure adverse impacts are identified early and often.

o Escalation and policy iteration mechanisms to ensure issues detected are acted upon at portfolio and whole of gov levels.

What do you think?

What are the challenges you see, and what do you think needs to be done to improve policy management end to end? How might the APS Reform agenda help drive change, and how can we all do our part to improve things? How could we better deliver policy outcomes, and better public and community outcomes? How can we close the gap between policy and delivery? Would love to hear your thoughts and examples!

I want to acknowledge all the people who are contributing to this work, especially the folk involved in the Intended and Unintended Impact of Social Policy research project which is worth keeping an eye on!

Thanks for an excellent post. I hope this is the start of something truly transformative.

I wonder how we might support the “how” of good policy with the actual design of policies. Like, why shouldn’t policies be run as experiments, or ‘pilots’?

Perhaps all policies should be thought of as “safe-to-fail experiments”, and we should design them accordingly. The Cynefin “complex domain action form” (Cynefin is so nerdy 🤦🏽♂️) is a good start:

https://tinyurl.com/cynefinform

Also, perhaps we can broaden our idea of policy to include the decisions we make (or don’t make) closer to the work of delivering services. Policy as something we are continually co-creating.

Here’s a short paper about this idea. I would really value your impressions:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zZNjlpbN15yitFB0qd7Si156OqFnRXc9QirxCnsreSc/edit?usp=sharing